- Categories:

A Q&A With Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Author of July’s #1 Indie Next List Pick

- By Emily Behnke

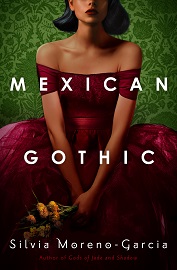

Independent booksellers across the country have chosen Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia (Del Rey) as their number-one pick for the July 2020 Indie Next List.

“Creepy and romantic, Mexican Gothic is easily one of my favorite books of 2020,” said Tyrinne Lewis of Rakestraw Books in Danville, California. “Upon receiving a strange letter from her cousin, Noemí Taboada goes to investigate the happenings of High Place, a decaying manor filled with secrets, and is plagued by terrifying dreams and visions. Moreno-Garcia delivers a fresh take on a classic gothic novel that will grab your attention from the very first chapter!”

Here, Bookselling This Week discusses Gothic novels with Moreno-Garcia.

Bookselling This Week: Where did the idea for this book come from?

Silvia Moreno-Garcia: This novel was inspired by several things, one of them being a real town called Real del Monte, located in the mountains of Hidalgo. It was an important mining center and it’s nicknamed “Little Cornwall” because of the British mining operations that took place there in the 19th century. Because of that history, it has a specific kind of architecture. It doesn’t look exactly like other Mexican towns in the area. The other thing that it has is an English cemetery, which, when I visited, looked like something out of a Hammer film. I thought about that cemetery for a while, just kept it in the back of my head, and when I was thinking of what to write next, it came back it came back as a visual idea. So, that was one of the inspirations, and the other inspiration was the mid-20th century Gothic novels, which most people tend to recognize as paperbacks with a cover of a woman running away from a castle at night in a flowing gown. There are other elements that inspired me, like horror films of the time period — black and white horror films, Hammer films, that kind of thing.

BTW: Noemí and her cousin Catalina repeatedly reference Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, in addition to fairy tales, like Snow White and Sleeping Beauty. Why did you decide to incorporate these aspects?

SMG: Because I was interested in the cultural legacy of Mexico, and specifically in this town, in these British mining operations. It’s not the only place in Mexico that had, and has still, European mining operations going on. At first, this one was mined by the Spanish and then it was mined by the British. And I was just interested in seeing what happens when somebody comes in from another part of the world and begins exploring the local resources, the local population. Normally, they just leave when the resources run out or something doesn’t go right, when a war or conflict interferes. But the scars that that leaves are great. Mexico and all of Latin America have systematically been plundered for decades in one way or another by foreign powers, so this was just one part of that plundering.

I think most people know that there was a Spanish Conquest. I think they think that once there was a war of independence [but] in all of Latin America, things didn’t just end in 1800, where everyone was free and happy and nothing bad ever happened again. After the revolutionary movements in Mexico and other countries, it’s not like everybody just shakes hands and goes on their merry ways. It kept going on, and sometimes one power is substituted for another power, one colonial power takes over another one.

BTW: This book also addresses the Gothic trope of the frail, suffering woman. Were you aiming to respond to any Gothic contemporaries?

SMG: Not any books in particular. There’s what people call the true Gothics, which are 19th-century Gothic novels, and then scholars usually refer to the mid-20th century novels as the new Gothic romances. They don’t consider those to be “real” Gothics. But when you talk about the 19th-century works, they’re divided into the Male Gothic and the Female Gothic. There’s some contention surrounding the terms, but it has generally been accepted for a long time that these are the two categories. The Male Gothic has supernatural elements or higher elements of terror, and the story takes place in a cruel and unforgiving universe. Meanwhile, the Female Gothics don’t have supernatural elements. The protagonist is a woman, somebody who is both a victim and a heroine at the same time. Ellen Moers considered the Female Gothics a “coded expression of women’s fears, of entrapment within the domestic and in the female body.”

I’m not trying to say in my book everything that came before me is bad and these tropes are bad. I’m just interested in the way that certain narratives play and the way that certain women are deployed, and that’s why these things appear in my novel.

BTW: In terms of tone, the horror in this book stems from not only supernatural elements, but that of real life as well. Howard Doyle believes eugenics; there’s considerable emotional abuse in the household; and the women of the house are under the near-constant threat of sexual violence. Why did you decide to blend these elements?

SMG: Gothics have certain narrative elements, which are the reason why people look for them, I think. One of them is the isolated location, another is the domestic sphere, another, at least in the new Gothic romances, is an element of romantic interest. All these tropes that developed and became associated with that specific product, and were used for mass production. So, whenever you saw a book, their covers were very similar, their taglines were very similar. And then the plots were, too. These were the precursors to the modern romance novel, and they were mass produced. So we get these things that happened reliably: you get a crazy woman, you get something in the new Gothic romances that’s going to end up being a “Scooby Doo” moment, something that is not really supernatural. These are fun things to consume because as consumers we went looking for them for a reason, and they were packaged like that for a reason, but the thing is that it’s not that fun to have exactly the same thing as a reader all the time.

I wanted to use all these elements that I know and recognize and have seen in a number of media deployed in a way that people might be able to feel like they recognize some or all of it, depending on how much Gothic fiction they consume, but to also give it a bit of a twist to make it interesting to a modern audience. The old Gothic novels were not produced for a contemporary audience. They’re not necessarily talking in the way that someone in the year 2020 might find interesting.

BTW: Mushroom spores and mold are not only at the core of this book’s story, but they also work to build the house’s creepy, derelict atmosphere. Why mushrooms?

SMG: I have an interest in mycology. I like mushrooms — I find them to be really interesting organisms. They’re not one thing or the other. They're not a vegetable, they’re not an animal, they’re something else. They belong to a different kingdom, even though you can find them in the produce aisle. The variety of the form they can take biologically and all the things they can do is very interesting, too. Mushrooms have a history in terms of hallucinogenic mushrooms and how they’re used culturally. There’s a specific way in which we’re using a certain type of organism to do things like engage in some kind of religious or ritual behavior.

I actually published and edited many years ago a small press anthology called “funghi,” which was a collection of short stories about fungi, so this isn’t something new for me. I’ve been interested for quite a bit. Originally, I became interested because there is a movie called Matango, which is a Japanese movie about mushroom monsters, but there’s also a story that inspired it by William H. Hodgson called “The Voice in the Night,” which contains mushrooms. That’s when I started liking them and looking for stories that contained them.

I think mushrooms are one of those things that, aside from being interesting visually and in terms of taste, they can also be characterized by some of the things that they do. There are several types of mushrooms that have these parasitic qualities, and are kind of terrifying when you think about it. One of them is an insect I name in the book, and when I talk about those, I'm not making it up. The mushrooms do take over an organism and change its behavior. Whenever you have an organism that can take over another organism to change its behavior, I think it’s kind of freaky.

BTW: According to your website, you have a background in science and technology, and you wrote a master’s thesis on eugenics and women. How did this inform your writing?

SMG: Eugenics was a widely practiced and discussed movement, and it lasted for quite a long time. It took place all over the world, not just in England, but in the United States and other parts of the world, too. Eugenics isn’t always concerned with racial theory. It’s also concerned with women and physical ability, and all that kind of stuff. It’s a wide spectrum, but it often does intersect with race in some very interesting ways. Race mixing is one of the big anxiety concerns for Europeans and Americans. This idea that somehow this “tainted” element is going to come in contact with this pure white element.

The most interesting thing about eugenics, the reason I love the study of eugenics and not eugenics itself, was because it was a real science. It appeared in text books and there were journals of eugenic science. It was a serious pursuit. People tend to think that science is divorced from the social sphere, and that is why things like eugenics happen. When you say, “Well, you know, objectively speaking, we measured the cranium of minority populations and they must be dumber than us,” that kind of thought comes because there’s a lot of embedded values put into science — we’re saying science is objective, but science is not something that you can completely separate from the other spheres that you are engaging in.

Even today, we’re engaging in ideas precisely because we think that science is completely objective and completely separate from any other kind of concerns. A lot of eugenics is still embedded in our discourse and minds. For example, the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, which restricted immigration from Asia into the United States and was only encouraging immigration from European countries, was the result of eugenic thought. That same box of ideas is what people still deploy now to talk about immigration policy, economic policy, and science policy. Eugenics hasn’t gone away entirely, it’s just being deployed differently. And it continued for a long time in the United States — people were being sterilized in the ’60s and ’70s in certain parts of the United States, based on eugenics acts that had been passed in the early 20th century.

Even today, one of the undeniable legacies of eugenics thought is the forced sterilization of women who have been in prison, especially Black women in the United States. When we think that eugenics is something that belongs only to the past and that we got over it, this is not true. And then also when we think that science is completely objective and never makes any mistakes, that is also not true. That’s why we need to think about science and the social sciences at the same time.