- Categories:

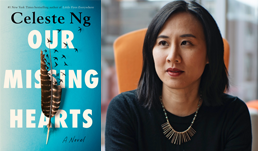

A Q&A With Celeste Ng, Author of October Indie Next List Top Pick “Our Missing Hearts”

Independent booksellers across the country have chosen Celeste Ng’s Our Missing Hearts (Penguin Press) as their top pick for the October 2022 Indie Next List.

Independent booksellers across the country have chosen Celeste Ng’s Our Missing Hearts (Penguin Press) as their top pick for the October 2022 Indie Next List.

Our Missing Hearts follows twelve-year-old Bird Gardner through his journey to find his mother, Margaret, a Chinese American poet, after she left three years ago during a time where the government began relocating children from parents deemed a threat to “American Culture.”

“Set in an uncomfortably plausible dystopian near-future, Our Missing Hearts pulls no punches,” said Allyson Howard of Invitation Bookshop in Gig Harbor, Washington. “Ng wrestles with how to find hope for ourselves and our children against forces that bend toward authoritarianism and nationalism.”

Here, Bookselling This Week talked about writing the book with Ng.

Bookselling This Week: Margaret, a poet unexpectedly proclaimed the voice of the revolution, has made an incredibly difficult decision as a parent — leaving home and cutting all ties with her husband and young son, Bird, instead of risking him being taken away to “protect children from environments espousing harmful views.” How did you craft her character?

Celeste Ng: These are questions that I was wrestling with myself — but with the volume turned way, way, way up. I was asking myself during a lot of the Trump presidency and then during the pandemic: how do I, as a parent, try to make the world better for my kid? How do I try and protect them from the things that are out there? I obviously am not in the same situation that Margaret is in, but those were the seeds of the questions I was seeing a lot of people asking themselves — what do we need to do to try and solve problems in the world, and how much are we really willing to risk? For Margaret, I tried to imagine my way into the position of someone who’s given this sort of authority or reverence that she didn’t actually ask for, and then try and figure out how she would handle that responsibility. I spent a lot of time reading about political movements and revolutions and what the people who were in them had to give up in order to lead those movements.

There’s a note at the end of the book about a poet named Anna Akhmatova who was living during the time of Stalin, and I came to her late in the process of writing the book, but her story seemed to resonate so much with Margaret’s. She refused to leave Russia and she kept writing poems against Stalin and against what was happening, and her son was put in jail because of that, and that really ruptured their relationship.

She was forbidden to write her poetry because she was seen as too dangerous, which I think is kind of fascinating. She’s a poet, right? But her work was seen as too dangerous. Stalin and his government forbade her from writing. She would write at night and then in the morning, she burned everything that she had written. Then the next day, she just rewrote from memory and started again and burned it the next night. That line is my retelling of the way that that particular woman was trying to balance what she felt her moral and artistic calling was with the obligations that she had to try and protect herself, protect her son, and to lay low. Those two warring impulses are very present in Margaret as well. That was what I was thinking about: what would these external pressures do to that very personal parent-child relationship?

BTW: The book’s title, Our Missing Hearts, is an emotionally charged piece of poetry and aspect of the movement displayed several times throughout the story. Can you share more about the process of making art to create change?

CN: I was thinking about [this] myself on a much smaller scale, especially during the pandemic. I was feeling kind of helpless and useless as a writer. If I were a doctor, I could be out there trying to actually help people. If I were a geneticist, I could be working on a vaccine and instead, all I've got is my laptop and I make up stories. I just felt very, very useless. Honestly, that’s the best word I can come up with and I started wondering, is this actually doing anything? Creating fiction and art in general — what is that doing for us?

I started realizing what was helping me get through this was reading poetry. I was reading books. I was listening to music that was kind of giving me hope. And it struck me that one of the things art can do is it can remind us of what we’re fighting for versus what we’re fighting against. It can hold open a space for change for the world to be better. I don't know that art can save the world by itself, but I felt like one of the things that art could do is to remind people that what they're living through is not the only way it can be, and it can shake you out of complacency. I started thinking about the ways art could serve as a wake up call or as a reminder to people of the things that they cared about.

One of the examples that I thought of was during the Trump presidency, when attention first came to the family separation at the US-Mexico border, a group called RAICES put up essentially little public works of art as protest. They put on street corners in several big cities a little cage and they put a little figure in there the size of a child that was wrapped in one of those mylar blankets, and they played a recording of real sounds that had been smuggled out of some of those detention centers. That got a lot of people thinking and paying attention to this issue in a way that maybe they would have blown off as they might ignore news reports.

Imagine walking to work and seeing that and hearing that; it’s harder to ignore that in some ways, because it comes in unexpectedly. I wanted to explore that aspect of how art can come at you sideways and bypass all the rationalizations you have and get you emotionally and kind of keeps alive this desire for change.

BTW: Our Missing Hearts really asks readers to challenge what we may become numb to — for example, seeing children quietly being removed from their families or blatant anti-Asian discrimination and violence happening out in public. What made this essential for you to include?

CN: I honestly had been thinking about this idea of children being taken from their families well before the Trump era. As a parent, you’d like to think you stand up for your ideals and of course you would do whatever you thought your principles dictated. The calculation becomes very different when you start thinking: would I still do that if it endangered my child? It becomes a much, much harder question. I was thinking about that dilemma: what would happen if your principles were asking you to do something that was also going to cause a huge sacrifice for you and your child?

When the pandemic happened, I started seeing these very blatant anti-Asian attacks happening. (Those are things that have always happened. They often go unreported and can go unnoticed.) There was one in particular that happened in New York. In the middle of the day, this Asian American was walking by and this man came up and just started beating her and nobody did anything. And that was what scared me, the fact that people just walked on by and nobody did anything — except for the doorman at the building that it was happening in front of? He came out and he closed the door. That was such a chilling and horrifying moment. How could you watch this happen? And your only action is to literally not look at it. So that’s one of the things that came into the book, those kinds of moments. It made me think a lot about the ways that it's a defense mechanism, and it's human and understandable that we want to not think about these things because they're so painful.

Again, art is one of the things that can make us pay attention. It’s often unexpected, it challenges us, and it’s very human and very personal. It forces us to confront the humanity of the person who’s made the art, and then to think about our own humanity. So, not to say that art will save the world, but I feel like you can only experience art in a very human, very individual way. And that’s a lot of what I feel like is missing when we go numb. When we stop thinking about other people as humans, it becomes very easy to look away from it. If we start thinking of them as humans, it's much harder to say oh, that’s not me. I can just close the door.

I should say, I never go into a book with a plan. But at the end, I look back and go oh, these are the things I’m thinking about. One of the things I was thinking about is the way that people lose their humanity. Sometimes it happens because they’re seen as Other, like with all of the anti-Asian attacks that happen in the book and real life it’s as though they’re not even people, we’re just not going to look at that. It’s not about me, we’re not part of the same group. They’re not human, in a way.

But it happens, too, from sort of the best of intentions. I was thinking a lot about the posters with George Floyd’s face on it. It feels so important to remember him and remember his face and I’m happy that people know his name, but it also feels in some ways like they’re stripping him of all the complexities of just being a human being. He’s not allowed to be a human being now in other ways. First, he wasn’t treated as a human being by the police that killed him. Second — now, in a way — many people don’t know anything about him. He’s just this emblem. It's so important to remember that he too, you know, and like Breonna Taylor, and the fictional Marie in the book, are also people. They were humans and they had particularities and they’re not just an icon. It feels really important to hold on to all of that humanity.

BTW: We see a future where schools and libraries are forced to remove many physical books and have implemented heavily curated and protected sites. We are in a time currently where some communities are already seeing these actions occur. What actions do you think independent bookstores and libraries can take to continue sharing stories in the fight against banned books?

CN: The fact that libraries and independent bookstores are calling attention to this and finding new things where they can, is so important, and I hope they keep doing it and feel supported in their communities. I feel like what we’re fighting against is this kind of authoritarian idea that there’s only one kind of story that deserves to be told. By their very nature, libraries and independent bookstores are open to everybody. Independent bookstores are not deciding what to sell because the CEO of the corporation is telling them to. They’re deciding what to sell because these are the books that they believe in and that they think the customers want and need. That's the opposite of authoritarianism in and of itself.

Besides that, I feel like continuing to talk about what’s happening seems like the most important thing and I hope people are starting to pay attention. I have been really heartened to see a number of stories speaking to many librarians around the country about the pressures that they're facing. That is a brave thing for librarians to do, to talk about it, because many of them are facing real legitimate threats to their profession, and threats to get fired and some of them are getting desperate. It feels again, in some ways, like making sure people can’t ignore that this is happening.

I can completely understand why some librarians or even bookstores might choose to just not have the conversation, not talk about it, and just not put those books up. I think it is really hugely admirable that so many people are saying, Hey, this is happening. Please pay attention. Please know that this is something I'm trying to fight for on behalf of everyone. It’s very brave that the librarians and journalists writing about this are making sure people know. It’s not a coincidence that I made the librarians some of the heroes of the book.

BTW: It is fascinating to see how quickly an idea can be ignited, whether it is one that is propelled out of fear or one out of hope. Ideas that ignite are at the core of the story. How does this play into the idea of a “good citizen” for your characters, and in our world?

CN: We're living in a very flammable time. Things, for better or for worse, suddenly, very quickly turn outrageous. and Sometimes that is really helpful, if something needs attention. Sometimes, it’s really disruptive because there’s things that are maybe not worthy of attention, and sometimes it's just distracting. Like if everything suddenly becomes a huge internet brouhaha, it's hard to tell sort of what feels important. The way that I feel like that intersects with the idea of citizenship is thinking and having judgment and taking a moment to pause and say: is this something that really matters? Is this actually in alignment with what I think our country is supposed to be and do? And am I helping that go along?

What this really comes down to for me is the need for context. A lot of times those outrages happen, and they almost sort of happen in a vacuum where you don't have the full context of what the story is and often when you have the full context, it’s a lot less inflamed than it might have seemed at first. You see one tweet or one comment is taken out of context again, and it’s like how dare you say that? Then you get the wider context and often the situation is more nuanced. One of the things that I've been thinking about in the book is the need for that context, the need to kind of understand where people are coming from, why they think the things that they do, and then to take that whole context and all the nuances in it and not flatten out the narrative. Which is what often happens in online discourse especially, but also not online.

BTW: Anything else you would like to share?

CN: I continue to be a cheerleader of indie bookstores just because I love them. I feel like after the pandemic, I recognized even more how important they are as it’s not just where you get your books. It's a place where you go when you connect, and you chat with people and you find new stuff that you wouldn't have found. That's my experience whenever I go to the bookstore, trying to get one book and end up with five because I'm talking to the booksellers and seeing what they put on the table. So that idea of, let's give more context — let’s give more stories. Let's enrich the picture and give you more voices to listen to. I feel like it is so important, and it's part of why I'm really grateful for indie bookselling.