- Categories:

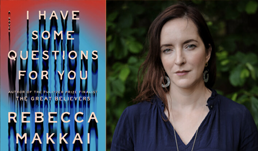

A Q&A With Rebecca Makkai, Author of March Indie Next List Top Pick “I Have Some Questions for You”

Independent booksellers across the country have chosen Rebecca Makkai’s I Have Some Questions for You (Viking) as their top pick for the March 2023 Indie Next List.

I Have Some Questions for You follows film professor and podcaster, Bodie Kane, as she returns to guest teach at the boarding school where her former roommate was murdered their senior year as a new podcast emerges reopening the case.

“Rebecca Makkai redefines the campus novel for our current times," said Kira Wizner of Merritt Bookstore in Millbrook, New York. "This was deftly written with such a fresh perspective and clever deconstruction of a murder case, I walked around my apartment fully immersed, book in hand.”

Here, Makkai discusses her writing process with Bookselling This Week.

Bookselling This Week: True crime podcasts and docuseries are wildly popular! In I Have Some Questions For You, we see a twist on the true crime podcast story. The main character, Bodie, is unique — she was the roommate of the student murdered from almost thirty years ago, and is now a guest professor teaching a course on podcasts on the campus where the murder occurred. Where did this idea come from?

Rebecca Makkai: It’s a lot of ideas, right? For one, I was always going to write a boarding school novel. I, among other things, live on the campus of the boarding school where my husband teaches, and I’ve lived here for over 20 years. It’s a world that I know and it’s a world that I find fascinating.

Like everyone else, I’ve always been drawn to true crime, and podcasting is just the latest medium for that. Looking back, there was Dateline, America’s Most Wanted, the Unsolved Mysteries of my youth, but you can look back even to the way that murders were covered in the newspapers in the ‘20s — lurid! It would make BuzzFeed or TMZ embarrassed. So, there’s my general fascination with all of that, about why we would be drawn to these things.

Those two things came together along with a bunch of other pieces, like the #MeToo piece, or the idea of someone looking back on their own adolescence. All of these points of origin snowballed together into this book.

BTW: I love that. As a reader, I shared similar thoughts with the secondary character Britt early on, before she dove into the podcast, when she questioned the true crime focus of the series. She described this as, “I don’t want to be another white girl podcasting about true crime.” I wanted to hear more about that: why are we drawn to true crime as entertainment?

RM: It’s interesting, even some of the most popular true crime podcasts are starting to ask that. There’s a lot of self-examination, and a lot of conversation about why women in particular are drawn to hearing about violence against women. My theory on this (and this is completely unsubstantiated junk science) is that it’s evolutionary, in a way. If someone dies near you, you need to know everything about why for your own survival. Without even knowing why, we hear about something happening and there’s an I have to find out every single thing kind of instinct.

Of course, the problem is we didn’t really know those people. It’s different when it’s someone you know, and this has happened to you. When it’s a stranger, of course, we learn things from that. For instance, learning the signs of domestic abuse and what kind of guy you absolutely do not want to date, is an important takeaway from some of these stories for women. But at the same time, when there's living and surviving family members, podcasts, television shows, and online communities can turn this into entertainment in a very problematic way.

BTW: Bodie’s character is complicated as she toes the line of being a supportive (and objective) podcast professor, and leaning in to what she believes is the truth of Thalia’s murder and influencing her students’ true crime podcast. How did you craft her character?

RM: Great question. It’s layers and layers and layers. When you start writing a character, you’re writing about someone you don’t know yet. Maybe you’ve done a lot of thinking about them ahead of time, but it’s like a blind date the first few months or even the first year of writing someone. You have revelations about them as you go. Any shrink would say that any character in your dream is you, and I would say that any character you write is you.

I gave Bodie a few things in common with me, one of them being the year she graduated from high school (I was young actually, for my class). I’m not actually the same age as her, but I did graduate high school in 1995. That gave me a lot of cultural touchstones and the same amount of distance from high school to look back on, as well as being a scholarship student at a boarding school.

Other than that, there’s a lot of making this person intentionally different from you. You build and build, it’s like layers of paint. I’m not a great film buff, but this is the passion of Bodie’s life. I watched a lot of documentaries about film history just to know what she'd be talking about. That's part of it, too, but it’s fun. It’s been a while since I’ve worked in the first person, since my first book, actually, other than the occasional short story. There’s an intimacy with a character that’s really thrilling.

BTW: In the story, we learn about the complicated justice system and its red tape, which leads to some unconventional methods of discovering the truth. Bodie thinks to herself, “What measures did any of us have for the truth?” Can you share more about the process of searching for the truth with so many complexities (and emotions) involved?

RM: I did a lot of research because I’m not a lawyer, and I was not interested in the Perry Mason version of this. The reality is, it is next to impossible to even get a retrial, even with exculpatory evidence, even when the DNA evidence that put this person in prison is no longer scientifically valid.

I worked with a wonderful public defender from New Hampshire to be granularly accurate, and I was talking to her about hearings and retrials. At one point, she said, “I recently did get a retrial,” but then she said, “it’s the only time in my life and I think I’m the only living attorney in New Hampshire that got one.” The system is just not set up that way. Prosecutors don’t want to give up their convictions. Judges don't want to overturn convictions and jurisdictions. Police jurisdictions don’t want to change their assault rates or to admit that they fudge things or messed up. There’s just this tremendous power, and a lot of incentive to maintain the status quo. And I knew that going in, but then you spend years living in this and spend all this time researching and see the way the system was rigged.

BTW: I Have Some Questions For You covers #MeToo, racial profiling, cancel culture, and classism. Can you talk more about your inclusions of these topics?

RM: Yeah, it’s not how I set out. Every single time I say I’m going to write a really simple novel next, it just does not work out that way. In many cases, it was realism. It starts with this girl who died, and you're sort of led in by the intriguing story. But there’s an ugly dark side to all this stuff; if the wrong person is in prison, how did that happen? Incarceration disproportionately affects Black men. That’s going to be part of the story. And the class divisions in a place like a boarding school. There are absolutely class inequities. The new novel starts to become thematically about those things — about whose story gets told, whose story is believed, who has the power of narrative? Before I know it, I’m writing a novel about class, race, gender, and the ways violence against women gets absorbed into the culture.

I was thinking about this novel for a couple of years, but I started writing it in early 2019 within that first wave of #MeToo. I was really surprised that #MeToo was not shy about big, big things, but it was also about how people were treated on their first job, or in high school, or daily harassment. There were things that happened in high school and I thought it was my fault. Looking back and seeing that I was not the only one who had problems with stuff like that. It was a problem. No one would put up with that now. A lot of people were having that kind of reckoning [while I was writing].

BTW: You’re about to begin your book tour! How have independent bookstores played a role in your life?

RM: Every event for every other one of my books has all been in or through independent bookstores. From the beginning, that’s who advocated for my books. I don't tend to look at sales on a granular basis anymore, but I could look and see the kind of digitized map of where books were selling. Later I realized it’s one or two independent booksellers in that area who make it happen. I continue to have experiences like that, where one bookseller in one store has handsold pancake stacks of a book.

I've made really good friends with a lot of booksellers, which is a blast. When I'm in St. Louis on tour, I’m in conversation with Shane Mullins at Left Bank Books. He's someone who I've known for years, and who at an early reading where hardly anyone showed up, handsold the hell out of the book afterwards. I get so excited when I get to see him at a conference or in St. Louis, just in the same way that I have friendships with authors that I've met along the way.

When a new book comes out, it’s indies making sure that your last one was in stock or going, “if you liked this did you know she has other books?” It’s weird, The Great Believers was such an amazing book for me, for my career. It did so much for me, and I'm so attached to that world and those characters because of the depth of research that went into it about the AIDS epidemic, and the people I talked to before and since. I feel this weird sense of betrayal talking about my new book and doing stuff with my new book, but to know that this book might actually lead more people to read that one? That helps a lot.