- Categories:

A Q&A With Alyson Hagy, Author of November’s #1 Indie Next List Pick

- By Liz Button

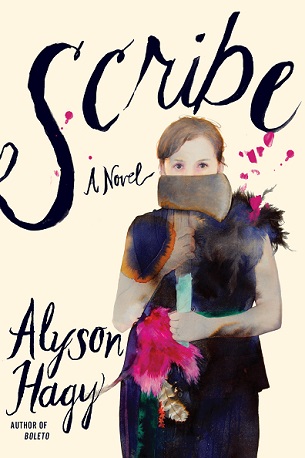

Booksellers have chosen Alyson Hagy’s Scribe (Graywolf Press) — part historical fiction, part post-apocalyptic saga — as their number-one pick on the November Indie Next List.

Hagy’s new book, which booksellers have also chosen as their number-one book for the Winter 2018-2019 Indie Next List for Reading Groups, draws on traditional folktales and the history and culture of Appalachia to illustrate a tale about the power of storytelling. In a post-civil war world ravaged by disease, the book’s central character lives on her family farm after the death of her sister, bartering her writing skills for subsistence while a migrant group known as the Uninvited set up camp on her fields, over which local land boss Billy Kingery keeps a watchful eye. One day, a strange man’s request for a letter triggers a reckoning with her troubled past, setting off events that culminate in a harrowing journey to the crossroads to deliver it.

Hagy’s new book, which booksellers have also chosen as their number-one book for the Winter 2018-2019 Indie Next List for Reading Groups, draws on traditional folktales and the history and culture of Appalachia to illustrate a tale about the power of storytelling. In a post-civil war world ravaged by disease, the book’s central character lives on her family farm after the death of her sister, bartering her writing skills for subsistence while a migrant group known as the Uninvited set up camp on her fields, over which local land boss Billy Kingery keeps a watchful eye. One day, a strange man’s request for a letter triggers a reckoning with her troubled past, setting off events that culminate in a harrowing journey to the crossroads to deliver it.

“I’m sure many book lovers among us would bemoan the lost art of letter-writing if given the chance. Alyson Hagy’s short novel Scribe returns us to a time when the written word was sacred — in an alternate timeline, to be exact,” said Sarah Crossland, marketing and communications director at New Dominion Bookshop in Charlottesville, Virginia. “After a civil war and an epidemic have ravaged the Appalachian region, one woman has become famous for her almost mystical ability to transcribe thoughts and emotions onto paper. Part historical fiction and part post-apocalyptic saga, Scribe finds the perfect alchemy between Cold Mountain and The Leftovers.”

Hagy, who was raised on a farm in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, is the author of seven other works of fiction, including Boleto (Graywolf, 2013). She has been awarded fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Christopher Isherwood Foundation. Her work has won a Pushcart Prize, the Nelson Algren Prize, and the Syndicated Fiction Award and has been included in Best American Short Stories. Today, Hagy lives in Laramie, Wyoming, where she is a professor for the creative writing program at the University of Wyoming.

Hagy, who was raised on a farm in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, is the author of seven other works of fiction, including Boleto (Graywolf, 2013). She has been awarded fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Christopher Isherwood Foundation. Her work has won a Pushcart Prize, the Nelson Algren Prize, and the Syndicated Fiction Award and has been included in Best American Short Stories. Today, Hagy lives in Laramie, Wyoming, where she is a professor for the creative writing program at the University of Wyoming.

Here, Bookselling This Week speaks with Hagy about her new book, which Kirkus, in a starred review, called “timely and timeless.”

Bookselling This Week: Congratulations on booksellers choosing Scribe as their number-one pick for the November Indie Next List. How did you feel when you heard about it?

Alyson Hagy: I was numb and surprised. I’m not a young person, so I remember when IndieBound was established, and I keep pretty close tabs on those lists because they really helped me think about what I might want to read and what I should know about. So to be part of it is just head-spinning, and to be number-one is beyond anything I ever thought possible. When you write a book, you’re in the bubble of your characters and your situation, and I, at least, don’t ever really know how people might react. I think Scribe is an odd, knotty little book, so the fact that it struck some sort of chord with readers is a wonderful surprise for me.

BTW: How did you get the idea for the book?

AH: I grew up in southwest Virginia in a place that looks almost exactly like the setting of the novel. I was driving from Charlottesville to my parents’ farm in Job, West Virginia, on the backroads and passing all of these abandoned, failing farms that I think were great and thriving in the late 19th and most of the 20th century and aren’t really anymore. And I started imagining what those communities must have been like, particularly the bartering and sustainable communities that would have been there; they would have been pretty isolated. And I just started thinking about it in a different way: I asked myself, what would happen to someone who was literate in a culture like that, who couldn’t make wagon wheels or weave rugs or raise sheep or whatever very handily? And once I asked myself that question, my imagination just started to tumble and spin and these pieces started coming together for me pretty quickly. But they were definitely in the shape of a tale, not a more realistic work of fiction, if that makes sense. And that’s different for me.

BTW: Story and myth are very important in Scribe in terms of the book’s format as well as the pervading mythical elements. Why write this “tale” as opposed to a more conventionally formed novel?

AH: I was trying to do something different; I’ve been an American realist for such a long time, so if I’ve been at all successful doing that I’m really pleased. I still don’t entirely know where the urge came from. I just wanted that awe that I felt as a really young person listening to people tell strange stories where it was ok that they didn’t make sense, that were just so strange but you were captivated by what was happening within. You didn’t need them to be exactly like your real world. Fairy tales are an example of that, and tall tales — the more outlandish the better. When I was a really little kid, I cut my teeth reading the Bible and going to church pretty much every Sunday, and the Bible is filled with odd stories.

BTW: In your research, did you look back at the history, folklore, and myth of Appalachia?

AH: Only a little bit. Honestly, I told folks at my first event recently that this was the one novel where I really didn’t have to do any research. I grew up there and this stuff is just sort of in my bones. I have, as a writer, spent a fair amount of time, particularly in my short stories, trying to think about how stories function, how they fall apart, how they come together, how they’re retold or borrowed, and for whatever reason, when this scribe character came to me, it was just going to allow me to continue to think about those themes in a way. But I was mostly swept away by the idea of someone who would write letters for other people, which I think was a real thing. I should say here, I’m so old, I still remember the remnants of the barter culture post-World War II, post-Depression. I grew up in the ’60s and ’70s, and my father was often paid in goods instead of money, and then my parents grew up in the Depression, when it was all barter.

I also come from that Scotch-Irish-African American mish-mash in Appalachia where people use stories to convey everything about their communities — where they think their communities are wrong, where they think they are strong; there’s a great sense of humor. I did go back and look at one of the collections of the Jack Tales just to remind myself of some things, and I borrowed shamelessly from a couple of those tales. I also borrowed shamelessly from my own family’s mythologies, some regional stories, and some indigenous stories. I’ve been doing that kind of work a little bit in my short fiction, but again, having this letter-writer write other people’s sins or narratives out for them allowed me to really run the mile with that idea.

BTW: Toward the end of the book, the letter-writer says, “It was all a writer could do to lay out the consequences of a person’s choices…Let him hear exactly who he is, and who he might yet become.” Do you think stories hold this same power today, to show us how to be better?

AH: Yes. I don’t usually think about it in terms of morals; that line just flowed from the pen, but it didn’t come in the first draft. It came later, when I started to begin to understand a little better what I was doing. But I thought, gosh, that’s why we should be studying literature, that’s why empathy in literature is so important, because we’re all making choices all the time. We imagine how we might behave under duress but we don’t really know, so stories can help us practice those decisions. And I think that they are absolutely as necessary now. It’s really interesting for me — the more political we become, the more we are able to create our own narratives moment by moment, whether it’s on Facebook or composing autofiction or whatever. It reminds you that these narratives are so powerful and so essential for the creation of community or the destruction of community, if you want to use them that way.

BTW: Do you consider yourself a “scribe”? Why do you write, personally?

AH: An old mentor of mine said many, many years ago that it was his opinion that writers fell into one of two camps, prophets or scribes, talking about people who were writing really politically engaged fiction. At the time I thought to myself, you know, I’m more the recorder as opposed to the firebrand visionary. I don’t know if I’ll always stay that way but, yes, I feel like I have been the watcher and the observer of my world more than the leader and creator of visions.

BTW: What has your experience at indie bookstores been like, both as an author and as a patron?

AH: I grew up in the back of beyond country, so we didn’t have bookstores. The library was my absolute favorite place to visit. I went to graduate school at the University of Michigan in the early ’80s, so the original Borders was in Ann Arbor at the time. I had never seen such a palace of books, new and used, and I had never been around staff who knew fiction and religion and history. It was just incredible and I would go in several times a week. I didn’t know what had been missing in my life.

Here in Laramie, Wyoming, we have this really unique, very small store called Second Story Books. It’s located in a former brothel and has been run and managed by a series of very smart, book-loving people who just keep all kinds of literature available. Second Story Books has been a different kind of anchor to me. It’s so wonderfully idiosyncratic; you never know what you are going to find on the shelves because it is so completely determined by the taste of whoever the manager is or whoever the staff person ordering the books has been. So that’s very cool, I think.