- Categories:

An Indies Introduce Q&A With Oscar Hokeah

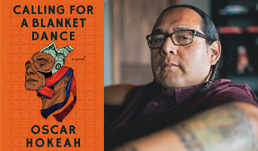

Oscar Hokeah is the author of Calling for a Blanket Dance, a Summer/Fall 2022 Indies Introduce adult selection, and August 2022 Indie Next List pick.

Oscar Hokeah is the author of Calling for a Blanket Dance, a Summer/Fall 2022 Indies Introduce adult selection, and August 2022 Indie Next List pick.

Hokeah holds an MA in English from the University of Oklahoma, with a concentration in Native American Literature. He also holds a BFA in Creative Writing from the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), with a minor in Indigenous Liberal Studies. He is a recipient of the Truman Capote Scholarship Award through IAIA, and also a winner of the Native Writer Award through the Taos Summer Writers Conference. His writing can be found in World Literature Today, American Short Fiction, South Dakota Review, Yellow Medicine Review, Surreal South, and Red Ink Magazine. Oscar Hokeah is a regionalist Native American writer of literary fiction, interested in capturing intertribal, transnational, and multicultural aspects within two tribally specific communities: Tahlequah and Lawton, Oklahoma. He was raised inside these tribal circles and continues to reside there today. He is a citizen of Cherokee Nation and the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma from his mother (Hokeah and Stopp families), and he has Mexican heritage from his father (Chavez family) who emigrated from Aldama, Chihuahua, Mexico.

Calvin Crosby of The King’s English Bookshop in Salt Lake City, Utah served on the panel that selected Hokeah’s debut for Indies Introduce. “Far more than merely the story of family, this amazing novel uses words to evoke the power of being part of Tribe and the ‘medicine’ it can create. Hokeah writes from the depths of his peoples’ history with a clear voice, imagining characters so beautifully formed that you may forget the book is fiction.”

Here, Hokeah and Crosby discuss Calling for a Blanket Dance.

Calvin Crosby: When did you know you wanted to write this book? And what was the experience of putting the novel together like?

Oscar Hokeah: It’s been quite the journey. The earliest chapter, Quinton Quoetone (1993), was written as “Got Per Cap?” back in 2008, when I was a student in the BFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA). I wrote it to capture what it was like for young Kiowas when we obtained that particular per cap money. And this is a part of the Native experience, getting what we call a “per cap check” from the tribe. It was later titled “Our Day” and published in American Short Fiction in 2010. So the earliest chapter was written 14 years ago.

Then I wrote another story called “Time Like Masks” which would be published in South Dakota Review in 2011. It’s now a chapter, Hayes Shade (1986), in the debut. Once I wrote this second story, I started to think about writing a novel-in-stories — similar to Elizabeth Strout’s novel, Olive Kitteridge — since both stories involved the same character.

There were many ups and downs with this book. In graduate school at the University of Oklahoma, I went through a writer’s block so I didn’t start adding more stories until after I graduated in 2012. I pulled together a novel-in-stories that I called “Reflections on the Water,” and more or less it was a cross comparison between a son and his mother. But I shopped it around to agents somewhere around 2013 (it’s all a blur now), and I wasn’t able to find any takers. So I stopped writing again. Defeated. I gave up. I didn’t write anything for years. Then in 2015 I had just left a work situation that played out like a movie. Sometimes life is stranger than fiction. So I decided I would write a full-length novel about this peculiar situation. After I wrote the first draft, in 2016 I had an old professor reach out to me and ask a simple question, “What are you working on?” I told him about the “stranger than fiction” novel, and then I started thinking about the novel-in-stories. Suddenly, I decided to implode “Reflections on the Water.” Why not? I had nothing to lose. The first version didn’t work out so it gave me permission to think of the theme differently. That’s when Calling for a Blanket Dance was born.

I pulled old stories out, and added new ones in. Suddenly, I had what I call a “decolonization narrative” or what most people might call a “transformation story.” For Natives, the process of decolonization is an important topic that we discuss profusely. Once I gave myself permission to start over, I realized I wanted to write a story about how Native people overcome obstacles that often plague the working class. Or what I like to call “the working poor.” For us, these societal issues are tackled through a lens of decolonization, where Native culture becomes the solution.

Now I hope folks aren’t dismissive and try to call my novel a “novel-in-stories” or a “collection of stories.” Too often, critics turn themselves into colonizers and dismiss Native agency. Especially when we stumble on the first thing we can “say” about a novel. Quickly, we toss it into a bin so we can move onto the next thing. But for the close reader, specifically the Indigenous reader, we can’t forget each chapter is narrated by a different family member. It’s polyvocal. Because the polyvocality is designed to capture the totality of “tribal family” which is communal in essence, we MUST look at my debut as a novel. These characters are all the same person — each an extension of the other — so to dismiss Native ideology with the colonial gaze not only cheapens the genre I love so much (literary fiction), but it also invades upon an Indigenous author’s agency, as if in conquest.

CC: I found a unique rhythm to your prose that held me at a pace that no previous book has. How much conscious thought went into the overall pacing and how deliberate was the pacing of the chapters? Throughout the book, each chapter’s end seemed to allow a breath you were unaware of holding — was this planned?

OH: It was and it wasn’t, which is always a horrible way to answer a question, lol. I tend to write organically. I’m not opposed to structuralism. In fact, I’m a huge fan of plot. But what I tend to do is write the story the way my instincts tell me to write it. More or less, how the main character wants it written. I’m a vessel. The main character is the one telling me what to do. And as this happens I see patterns, structural patterns, like the ones you mention that tend to leave the end of a chapter with the release of tension. I think the characters let go of what they can’t control, and give in to fatalism. I notice my characters are often swept up into circumstance that are often larger than them. They wrestle with the circumstances and attempt to impose their will. Then as you mention, “allow a breath you were unaware of holding,” the characters turn over the pieces they can’t control to something greater than themselves. I think this is very human — to grapple with the current of a river until we learn to flow along with it.

CC: What does having Calling for a Blanket Dance published mean to you?

OH: It’s amazing to have my first book published. My very first book! Sometimes I have to hold the book in my hands and turn it over between my fingers just so I’ll know it’s real. The simple fact of having accomplished this after 14 years. 14 years! So much time has passed and so many ups and downs. It’s been quite the journey to reach fruition.

But it’s the intangible that’s the most important. I’ve dedicated the novel to my children and that’s no accident. Family history is Native history. This is how we document the real history of our tribal communities. It’s not a single, exclusive narrative, instead history is a web of histories between family members. It’s the stories we share about each other that make our identities. It’s a value that’s reinforced in our drums, songs, and rituals. It’ll “forever be about how we dance together,” as Quinton Quoetone says in the novel. And these same families that exist here and now are the same families that existed hundreds, if not thousands, of years ago. It’s because of the unique environment in which I grew up that allowed me to structure this novel off our Blanket Dances. And it’s an honor to bring this Kiowa tradition to the page.

CC: You have said your work with the Indian Children’s Welfare, is your way to “give back to the community that nurtured and embedded Indigenous values.” How heavily does this filter into your storytelling?

OH: The process of decolonization begins and ends with our youth. I’ve spent the last two decades empowering Native communities by way of engaging with at-risk youth. I think this is a path toward honor. I’ll try not to give away spoilers in the “transformation story” of the main character, Ever Geimausaddle. But it does end on a positive note. Now I’m a big fan of the bittersweet, so the ending rings true to life, I feel. I write what I call “autobiographical fiction” or we could call it “memoirist fiction,” in that I fictionalize real events, meaning I modify things that are true to my personal life and the life of friends and family around me. I feel like this makes stories unique, and entertaining. So I draw from my personal journey working with youth and use it as a means of empowerment for characters.

This is not only true in Calling for a Blanket Dance, but I do the same in my second novel and third novel. Now the second novel is in the polishing phase. I haven’t turned it into my editor yet (so let’s just keep this between you and me, lol). I’m tightening up the second novel. My third novel is in first draft so it’s very rough. But it also follows the same thread with youth focused empowerment. My writing will likely always have strong themes of family and youth work. That’s been my entire adult life, being a father and being a youth worker. Unlike many writers, I’ve not gone toward teaching creative writing classes. I’m not opposed to it and I consider it from time to time, but I’m always left on the fence. Largely, this is because I feel a need to help the community move through the process of decolonization. So it greatly influences the content of my novels.

CC: What has been the response of your family, from the Cherokee Nation and the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma, to the book?

OH: My family is super excited for the book. For the last year, every time I go over to someone’s house, they ask, “When’s the book coming out?” and I echo back, “Soon.” I’ve also run into folks in the community who’ve said, “I’m seeing your name all over the place,” and are excited to talk to me about the book. Or they’ll say, “Your that guy that wrote that book,” and I’ll kindly nod. I’m always excited to talk to folks and enjoy it when they approach me. I’m excited for when the book releases. I have two reading events scheduled in Tahlequah to engage with my Cherokee community, and I have one event scheduled in Lawton to engage with my Kiowa (and Comanche) community. If someone is going to write a novel about tribally specific people, then they should bring it straight to the community. Don’t be a coward. And not at an arm’s reach in a nearby city. Bring it right into the heart, where communities of color have access. I’m excited to talk with folks about the many facets of the main character, Ever Geimausaddle, and his very colorful family.

CC: What are your hopes for this book?

OH: I’d like for my debut novel to be a source of validation and empowerment for Natives — especially those of us living and surviving in poverty. This novel is an homage to the working class. Natives aren’t trying to stratify a system. We don’t want power over people. We simply want to keep our family members from falling victim to a moveable standard. I hope the novel can also be in advocacy for working poor people. The stresses of being at the bottom of the economic ladder often comes through in violence, neglect, addiction, and abandonment, which aren’t easy to cope with when historically our communities have been targeted and families fractured with each generation. It’s hard to build generational wealth when every behavior we have is considered criminal. This novel will be a great source of validation for anyone — regardless of race — who grew up in a poor and fractured community.

Calling for a Blanket Dance by Oscar Hokeah (Algonquin Books, 9781643751474, Hardcover Fiction, $27) On Sale Date: 7/26/2022.

Find out more about the author at oscarhokeah.com.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.