- Categories:

Indies Introduce Q&A with Josh Galarza

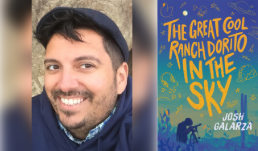

Josh Galarza is the author of The Great Cool Ranch Dorito in the Sky, a Summer/Fall 2024 Indies Introduce YA selection and a July/August 2024 Kids’ Next List pick.

Donna Liu of Kepler’s Books in Menlo Park, California, served on the panel that selected Lim’s book for Indies Introduce.

“This stunning and heartfelt debut starts off with Brett in a terrible mental place, coping with harmful strategies like binge drinking and eating,” said Liu. “Stick with it though, because you will care for Brett and the people around him so deeply, and if you’re anything like me, end up sobbing over the last few chapters. I absolutely loved it and wholeheartedly recommend it.”

Galarza sat down with Liu to discuss his debut title.

This is a transcript of their discussion. You can listen to the interview on the ABA podcast, BookED.

Donna Liu: Hi, my name is Donna Liu. I am a bookseller at Kepler's Books in Menlo Park, and today I'm here talking to Josh Galarza, author of The Great Cool Ranch Dorito in the Sky. It's coming out on July 23, and it's just one of the most incredible books I've read — definitely this year and maybe of all time. Let's be a little dramatic, because that is how much I love it.

Josh Galarza writes fiction and creative nonfiction, and is a multidisciplinary visual artist, specializing in printmaking and book arts. He splits his time between Reno, Nevada, and Richmond, Virginia, where he teaches at Virginia Commonwealth University while completing an MFA in creative writing.

Whew, that's a lot! You do a lot of stuff, Josh. You want to tell me a little bit more about some of the stuff you do? Or maybe stuff you’re doing right now?

Josh Galarza: Thank you so much for that incredible introduction. It means the world that you love the book, and I'm excited to get to talk about it with you. I actually think I have way too much on my plate as a grad student at Virginia Commonwealth. I love getting to teach the undergrads. I definitely don't have enough time for my visual artist practice right now, so I'm looking for a little more balance after graduation next year. But I do best when I'm busy, and I do my best writing when I'm under deadline. When I have pressure, I'll go into this fugue state in the middle of the night and miraculous things will happen. When I have all the time in the world — like I do this summer — I just play too much Mario Kart, so it's good be a busy boy.

DL: Okay! Let's dive into talking about the book. The first time I talk about this book to anyone new, there’s always a moment where they’re like, “Oooh, the title! That's a really cool title.” It caught my eye when I was first going through the list to see what was coming up. But tell us about how you came up with the title. Was it like a flash of lightning, or did you have to work on it?

JG: The title existed before the first scene was ever even written. For those who aren't familiar, this book is very much about processing and overcoming grief — or coming through grief, because I don't know if anybody really overcomes that. And I was working through some really intense grief at that time. Also — maybe bizarrely, because I was in my mid-30s by then — I have a giant trampoline in the backyard, and my favorite thing is to be out there at night under the stars, stargazing on my trampoline.

When I was grieving at that time, laying on the trampoline and crying — it was a very good place to be alone — I'd be gazing up at the stars. I feel like my education in astronomy was rather rudimentary, so I could pick out the Big Dipper or Cassiopeia, but most of these constellations I was making up. What I now know is the Summer Triangle, I was like, “Oh, that's a giant Dorito, that's pretty cool.” So I called it The Great Cool Ranch Dorito in the Sky. I also noticed that if you extend that out to another star you have this gigantic bird that takes up the whole sky, and I was like, “Oh, yeah, there's Daddy Condor.” Then underneath there's Baby Condor, who's flying safe under his wing.

So Daddy Condor and Baby Condor and the Great Cool Ranch Dorito. All of this evolved as part of this story. Daddy Condor became Captain Condor, Baby Condor became Kid Condor. These are important characters in Brett's life. Brett, the protagonist, writes his own comic book, and I think my obsession with the stars became his. That title was so absurd, I thought, “If I'm lucky enough to keep it all the way to publication, you can't walk past it in a bookstore and not take another glance.”

DL: I'm so happy to know that the trampoline has a basis in reality, because some of the scenes on the trampoline are among the most noteworthy, or emotional. They play a big part in the story. [The trampoline] plays a big part in the story.

Talking a little bit more about Brett: he has a very unique style, or unique voice. How much of Brett’s voice is yours? How did you develop it? Do you feel like you really captured the essence of Teenage Boy?

JG: Recently, one of my nonfiction mentors — Sonja Livingston, an incredible mentor at VCU — when she first saw my nonfiction, she was like, “This sounds exactly [like] the way you talk.” And I think that is by design. I learned early on with my very first and beloved writing mentor — Marilee Swirczek was her name, a beautiful woman that was beloved in the community — that I didn't know even what a writer's voice was. That's how green I was when I started writing. I didn't know I had any talent, or that I might actually achieve something with this. It was just a need to express myself.

I remember her saying to me, “I want to be careful with you. I want to refine what you've got. I want to refine your talent, but I don't want you to lose whatever this magic is in your voice.” I'm like, “This is a really nice compliment. I don't know what you're talking about, but I'm just going to take that in, and eventually I'll understand it.” And I think I do now, because no matter who I'm writing, I feel like that voice is really, authentically my own, and for any character I'm just pushing away from that center, that core of myself in particular directions.

So, Brett, he's very bro-y. And I'm very bro-y with my bros — especially my straight bros. I'm very swishy with my gay friends (I'm gay). These are all really natural parts of me, and so I just push a little further in that bro-y direction for Brett. I'm writing a new character now, and he's far more serious and very academically minded and very literary. So I'm just pushing him in that direction, which you'd see more in my personal essays. He sounds more like a literary guy. I think there's this basis in truth of who I am, and my personality, that I was lucky enough to have a mentor that was helping to shape that but preserve it, and now it's just really ingrained.

DL: I remember when I was reading at first, it definitely took me a moment to get into Brett's headspace, and his unique voice. But after that I was just like, “I don't know, the kid has a turn of phrase, right?”

JG: Oh, thank you!

DL: He says some really interesting things.

JG: Sometimes I think he's too clever.

DL: Maybe! Maybe a little too clever for his own good. But one of the things I really liked was the idea of the “just right words,” about finding the words that capture the essence of something. So one of his just right words is “Mestizo,” and he learned it from Gloria E. Anzaldùa. I would like to hear more about how you conjured Brett's identity, and all the different parts of it, because he's a very complicated kid with a very complicated history.

JG: I went back to college in my mid-thirties. I had left a career in Montessori — I taught young children for about 15 years. You think when you go back to college in your mid-thirties, you're showing up fully formed. And the reality was, I don't even know if I was completely actualized as a human being yet. I had so much to learn, and I was so incredibly stimulated by this consciousness-raising journey that I was on, and so grateful for it.

I was a lifelong learner, I love learning, and there was this whole new world opening up to me with cultural and critical theorists, social critics. Reading these books that had been around for most of my life, or since before I was born, but if you're just going through life living your little life in your little town, you may never have reason to stumble upon them.

I was in my first theory and criticism class, which was so challenging. There were people crying in the hallways about ruining their 4.0s. It was that type of class you had to take, but it was the hardest class of the program. I was scared, too, but I was so excited by what I was reading, and Gloria Anzaldùa was one of those authors.

So on my mom's side, these are white people, but on my dad's side my grandfather's Maya, and my grandmother's Mestiza. My dad was the only one of his siblings to even be born in the United States. There's a lot of history there that I wasn't terribly connected to, because I was raised primarily by the white side of my family. Gloria Anzaldùa speaks about racial amnesia — and in my case, stumbling upon her work and being in a rich environment of thinkers — I really started to ask questions about where I come from, my past and my connections to it. Initially, what's so interesting to me, is white supremacy is so successful at conditioning us that I remember starting out thinking, “Maybe I should make Brett white. He's going through a lot, I think writing about disordered eating and body liberation is very challenging on its own. Maybe bringing race into the picture is going to be too complicated in the story, and I feel overwhelmed.” And I felt overwhelmed in my own exploration about my past, and who I am.

Luckily, I had incredible mentors and friends who were helping me to see what was right in front of my face, which is, “How could you disrespect yourself that much?” What I eventually came upon was: Yes, it's more complicated. Yes, it brings new challenges into the story if I write Brett as Mestizo. And yes, I'm learning, but so is Brett. I can write a Mestizo character — a character who looks like me, who has an ethnic background similar to my own. I can do that in a way that feels a hundred percent real and authentic to who I am, which is someone just like Brett, who is learning and exploring and understanding.

And from then on, it was just taking great feedback from my agent, and eventually my editor — Jess Harold — who just asked the most incredible questions, and let me stew on those questions. She wasn't pushing me, but she was asking the right things that allowed me to develop that part of who Brett is, and instead of making his life too complicated, it simply made it richer. I'm so grateful for that, because it took away whatever fears I might have had about showing up as all of who I am.

DL: I love that you were able to find such a genuine, authentic voice and identity for Brett, because I think it's going to really resonate with readers.

And I didn't give you this question, but I believe you have the capability to answer it. I wanted to talk a little bit more about the disordered eating that Brett goes through, and what was it like writing that? Do you think that it was more challenging because your main character is a boy, and a lot of the time the disordered eating narratives we get are for young women — women in general? So I'd love to talk about that.

JG: I recognized in hindsight that I sort of began a path of disordered eating and body dysmorphia in my teens around Brett's age. At the time I didn't have any clue what was going on. There was a lot of media out there for young women, as you say, and because of the time in history — this is the mid-to-late nineties — there were a lot of flippant attitudes towards disordered eating. It was almost just an expectation for young women especially, and often a joke in media, which is so disturbing in hindsight. Every once in a while, you'll watch that old movie you loved as a teen, and you're like, “Oof, that has not aged well,” right? So the messaging I was getting was very much that this is an issue that affects women, so I couldn't even recognize what was happening within myself, especially as I got into my twenties, where the behavior really became about extreme healthism. That has a name that I know now, and I absolutely did not know when I started treatment and started writing this book: orthorexia.

So I was pretty severely orthorexic, primarily. The thing about that that is so insidious is it looks like you're just a healthy guy. You just love to go to the gym. You just love a workout. You just love to eat clean. You just love to be healthy. You're being praised for that, and all of that is in service of trying to live in a body that society tells you is the right kind of body. Of course, something I know from my own experience is that men are maybe not as affected in society by the typical standards, and certainly not the male gaze, the way that femme people and women are. But that doesn't mean that there aren't certain expectations about what our bodies are supposed to be like — what good bodies are like, what moral bodies are like, versus immoral bodies and bad bodies.

And I had no clue until my mid-30s, going into college, that this all has its roots in racist white supremacy and patriarchal society. You're looking at all these systems that were always around you, shaping who you were, but you couldn't even see them. Suddenly I'm seeing them everywhere I look. And I thought, “how different could my life have been if I'd have understood what was happening to me 20 years ago, rather than it escalating and spiraling until it was something that I finally did recognize.” It morphed into bulimia, and that to me was very like, “That has a name. I know exactly what that is. I'm really freaking out. I'm worried. I'm afraid.”

To add context, going back to college, I had access to incredible counseling services. I just had to work up that courage to walk in that door, and that was hard. But when I did, immediately I was surrounded by an incredible treatment team that were very invested in me, and I was at a point in my life where I was very ready to do that work. I was sick of destroying my life — which is really what I had done at that point — and I was ready to rebuild. I recognized an opportunity.

Recently I was reading Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl, and that's all about how do we make meaning out of, you know, the most horrific things that can happen to us — in his case that was the Holocaust. And I recognized some good could come out of the suffering. Some good could come out of the pain that I had experienced. That's going to be healing for me, and it could help somebody else to have a wholly different experience, just because you planted some seeds in their mind as a storyteller, that then they decide to go explore and know themselves, and the world, and the way they fit into it a little bit better.

DL: Thank you for that. That sort of gets us into our next question, which you know is about some of the other characters, including my personal favorite, Mallory. Who you call in the book, “a total Mr. Miyagi of being in the body she’s in.” Just a badass, a completely amazing character. Tell me a little bit about writing the different relationships that Brett has, including with Mallory, Reed, and some of his other parental authority figures, Evelyn, of course. Which was your favorite relationship to write?

JG: You hit the nail on the head. Mallory is my very favorite character in the book, and definitely my favorite to write. I'll start by simply saying, conversely, that Evelyn was challenging. Evelyn is inspired by my own mother, who had a pretty horrific illness and died in my teens — a lot of stuff I hadn't processed or worked through. She was also inspired by my very first writing mentor, who I mentioned, who was taking me under her wing, and instilling so much in me, and treating me with so much love. She was a very mothering person, and she treated a lot of writers in her life that way. So the grief I was experiencing at her death, which was very much like bringing up grief about my own mother, that was painful and challenging to write and work through. But I knew I needed that. There was something healthy about that activity.

Conversely, Mallory is all about the healing. Mallory is incredibly empowered and incredibly independent. She has more agency than anyone in in this book, because she has more knowledge than anyone in this book. She has been in treatment long enough that she has learned a lot of the things I was learning early on in treatment, that have helped to develop her value system. Brett is very green, and his value system hasn't even had time to really develop fully because of his illness. And Mallory just is generous enough to recognize: here's a person in need — a boy who absolutely has no clue what's going on in the way that a girl might. Might it be in line with my own values, right, as a healing woman to take him under my wing and help him?

To me, she's a testament of how lucky any man is to be mentored by women. I was mentored by women throughout my Montessori career, as an artist, a printmaker, as a writer. And when I look back, I recognize these women were helping me be better in those endeavors, but they were helping me be a better human. And better humans produce better artwork. Better humans are better teachers. In a society that would try to strip as much humanity away as possible from a man, from a boy — which was definitely happening to me in my life, through all that conditioning — being mentored by women helps you to regain some of that, or to maintain it, or to hold on to some parts of you that you might have otherwise lost.

To me, Mallory could only have been female, because the cluelessness that a lot of men experience around these issues — Brett wasn't going to find that in a guy. One of my goals is for young boys to start to think differently about the girls and women in their lives, and to recognize the value that women as mentors have for them, and to think differently about their bodies as well, and the way that they might objectify them. So Mallory is serving a lot of purposes, and I'm proud of the fact that she's doing all of that while being a fully realized human herself, who has her own goals, her own values, her own hopes and dreams. She doesn't need to be doing this for Brett, but I'm grateful for the women in my life, and especially in treatment, who understood better than I did about fatphobia and about body liberation, and who helped me to overcome. She's very much representing that.

DL: I think that's great. I think also what is significant is that she's not the only person in Brett's life who's trying to help him. He has many figures in his life. One of my questions is: what do you want readers to walk away with? I certainly walked away with the idea that it's okay to ask for help, and it's encouraged, and it's necessary to ask for help. Because you don't have all the answers, and as teenagers, definitely didn't have all the answers. So you have to go to someone who has some of the answers, and then someone else who has some more answers, and a professional who has a lot of the answers.

I would love to hear if you have any plans for any of these characters in the future. Are you going to let them live in this book? And you know, be, or are you going to resurrect them for another go?

JG: I would never say never, because I just love these characters with all my heart, but I generally see myself as that type of writer who, in a very literary way, is always looking for the next challenge, or the next story. I do see this as a really well-contained story.

If I ever imagined a sequel or another book with these characters, I always imagine Robyn — who sort of plays a bullying character at school. She and Brett spar a lot, but they're both really clever, and eventually you recognize that these two are becoming allies, and friends by the end of the book. I always imagine theirs is the enemies-to-lovers romcom that I will probably never write. It started to make so much sense for me, because I knew from day one Brett has healing work to do. This book isn't about the boy getting the girl, even though he has his moments — like any boy would — of imagining what that would be like. I imagine that for him in the future, but that wasn't what this story was. And yet, when people ask me about his future, and when I think about it, I'm like, “Oh God, he and Robyn, they just make so much sense to me.” So I get a kick out of that, and once you read the book, and you get to know Brett and you get to know Robyn, I think you'll probably get a kick out of that, too.

DL: I would read it. A hundred percent. So if you ever write it, send it my way. Amazing! Well, I think we answered most of my questions, is there anything else that we didn't touch on that you would want the readers to know before reading the book? Or what do you want them to walk away with?

JG: What I want people to walk away with is two things: I want people to feel both empowered and validated. The validation comes in some of the hardest aspects of this book. It is a challenging book. It's very much a literary book. It's asking you to struggle through some tough topics. One of the things I definitely didn't want to do was a book that was so fat positive that it ignores the fact that sometimes, being in bigger bodies is hard. When I was in treatment, I had to make a real decision in my head like, “If I recover into a fat body, am I okay with that? And can I live with that?” And the answer was absolutely, yes. But that isn't easy every day. You know, some days you're on a flight and the armrest is like digging into your thigh. There's just so many aspects of being in bigger bodies that are challenging, and I wanted to validate that. It's okay to feel the way you feel when you might be struggling in a very fatphobic society.

I also just wanted then to say, “Okay, you can feel those things while also nourishing your body, respecting your body, celebrating all that your body does for you, valuing yourself and your body, no matter what form that takes, and no matter how that changes over the years of your life.” And I do think that that's empowering, right? That knowledge empowered me — a person who was working really hard to be in a particular type of body for all of my life — to suddenly say, “Actually, my body's job isn't to look X kind of way. My body's job is to create art, to write stories, to get me to the grocery store, to drive a car, and the way I look isn't really a factor in that.” That was a profound moment of change in me. I just want to provide validation in that way for readers, and plant those seeds, where they're questioning all the things they've been taught about their body, and how it's supposed to look, and why. Where does that come from? And maybe they can choose to reject that. And that's really empowering.

DL: Wow! For the listeners who don't know, Josh and I got to meet in June at Children's Institute in New Orleans, which was amazing. Really hot, but really fun! And you said some really great things about your experience as a debut author there, so I would love if you could share that with the listener.

JG: Absolutely. I think as a creative, as a writer, you're always anxious about how your work is going to be received, and I realized with this book I had to be kind of brave and bold. If you're going to be associated with this subject matter, and you're going to be this vulnerable as a human and as a creative, are you really ready for that? And you think that you are, and then crunch time comes, and you think, “What if the book actually isn't that great or what if people don't respond? What if I'm misunderstood?”

I think when you're writing challenging work, you can easily be misunderstood. So I'm so grateful for Indies Introduce and for the Children's Institute experience, because before you're starting to see ARC readers putting up reviews, you're getting this clear validation that all of your hard work — people do see it. People do appreciate it. To be a debut where your first big author event is on a scale like that, where you have an audience of just hundreds of people, that was really overwhelming, but so, so validating. Those moments where that fear still rises up, you get a bad review or whatever, you remind yourself: no piece of art is for everybody, and the people who need this book — thanks to these incredible booksellers who are working so hard to get it in the hands of readers — they're going to find it. And that was the goal all along, so it's really validating, but not in this egotistical way. I'm proud of the hard work it took to write a book like this, from a place of healing for the first time, rather than writing for years from that place of festering toxicity, and I'm so grateful, that others see the value in that.

DL: Absolutely. You know, this was such a fantastic talk, I feel like we could go on forever. But I think we're going to end it here. It was just so wonderful talking to you again and seeing your face after meeting up last month.

JG: A joy.

DL: Thank you again, so much for speaking with me today. It's been an absolute pleasure. Have a good rest of your day, and listeners, go out and read The Great Cool Ranch Dorito in the Sky, July 23. It is just fantastic. You're going to love it.

JG: Thank you, Donna. I appreciate you so much.

DL: Thank you. Bye.

The Great Cool Ranch Dorito in the Sky by Josh Galarza (Henry Holt and Co. BYR, 9781250907714, Hardcover Young Adult Contemporary, $19.99) On Sale: 7/23/2024

Find out more about the author at joshgalarza.com.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.