- Categories:

An Indies Introduce Q&A With Jennifer Savran Kelly

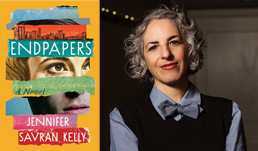

Jennifer Savran Kelly is the author of Endpapers, a Winter/Spring 2023 Indies Introduce selection.

Jennifer Savran Kelly is the author of Endpapers, a Winter/Spring 2023 Indies Introduce selection.

Jennifer Savran Kelly lives in Ithaca, New York, where she writes, binds books, and works as a production editor at Cornell University Press. Her forthcoming debut novel Endpapers won a grant from the Barbara Deming Memorial Foundation and was selected as a finalist for the SFWP Literary Awards Program and the James Jones First Novel Fellowship. Her short work has been published in Potomac Review, Hobart, Black Warrior Review, Trampset, and elsewhere.

Nikita Imafidon of Raven Book Store in Lawrence, Kansas, served on the panel that selected Kelly’s debut for Indies Introduce. “I was enchanted by the unfolding of Endpapers,” said Imafidon of the book. “Following a genderqueer bookbinder in 2003 New York City, Endpapers is about finding yourself among the chaos. When Dawn finds a mysterious queer love letter, her world opens, leaving her to question her relationships, gender, and the ways the world treats queerness. Savran Kelly’s writing is authentic and unique, luring readers into a world where everyone’s story is necessary to tell. Endpapers is a quick-paced novel that will stay with you long after you finish.”

Here, Savran Kelly and Imafidon discuss Endpapers.

Nikita Imafidon: What inspired you to write Endpapers?

Jennifer Savran Kelly: The original kernel of the idea came out of my first bookbinding workshop, at the Center for Book Arts in Manhattan. Our instructor told us that sometimes binders used to find personal letters hidden under the endpapers of books — the blank or decorated leaves that are usually glued to the inside front and back covers. The idea of someone hiding a personal letter in a place where it could never be found unless the book was damaged or destroyed struck me as both romantic and tragic, and it stayed with me for many years. When I decided to write Endpapers, I was excited to build a novel around this idea, but I didn’t yet have a story to go with it.

I’d also been interested in exploring queerness in my writing for some time, except I was afraid that if I tried to write a novel based around a social issue, it would turn into more of an essay or treatise. So I started by looking around for inspiration — mostly in photographs and books — seeking out personal stories that might spark ideas for a main character and for the person who wrote the letter she finds. Eventually, a vision started to form for Endpapers.

NI: The novel explores many themes, most notably the complexity of gender and sexuality. Why was this important for you to include?

JSK: I’m bisexual (or probably more accurately pansexual) and was out and proud during college, but I’ve been married to a cisgender, heterosexual man for about 20 years and have essentially been back in the closet for most of that time. I’ve been too afraid of what people might think — both my straight family and friends as well as the LGBTQIA+ community. I worried it would either make people angry or disgusted or, possibly worse, no one would believe me or they’d think I was just looking for attention.

For much of my adult life, I’ve also had an exploratory relationship with gender (for lack of a better word). I’ve always been clear that I’m not transgender, but there haven’t been any mainstream words for genderqueer or nonbinary until fairly recently, so I didn’t have a coherent way to understand my feelings. Plus, for a number of years, the question seemed to fade away because I was happy to present as conventionally female.

Then two things happened: violence and political backlash against transgender people and the whole LGBTQIA+ community began to rise and Trump was elected president. I felt pretty desperate to do something, but I shy away from protests and crowds, so writing seemed like my best way to speak out. I wanted people to know that they may have queer family members or coworkers or friends who stay quiet about their identities for a whole multitude of reasons — people they care about who are being personally affected by violence and targeted by harmful legislation. Because otherwise it can be just some abstract idea; people tend to act on issues that have a personal impact. At the very least, I hoped it would inspire people to think twice about their choices in the voting booth.

For the same reason, I made Dawn, the main character, Jewish. I’m Jewish, and growing up I never thought I would see antisemitism rise to such a frightening degree in this country.

NI: When I was reading the novel, the backdrop of New York City felt like a character of the story. Why did you decide to set Endpapers in 2003 New York?

JSK: Thank you. That was certainly my hope! I grew up on Long Island and lived in Brooklyn and Manhattan for a few years after college. I’ve always loved New York City and it’s where I learned how to bind books, so Endpapers is a sort of love letter to the city.

But more importantly, Dawn’s relationship with Gertrude, the person who wrote the mysterious letter, is central to the story. It’s through Gertrude that Dawn discovers a personal connection to queer history, which gives her context for what she’s going through in the present. I wanted readers to experience this along with her. So setting the novel in 2003 was partly a matter of logistics: I needed Gertrude to be alive when Dawn found her letter, and that placed Dawn roughly around the early 2000s. It excited me, however, because it allowed me to explore the relationship between two particularly oppressive times in US history — the 1950s New York that Gertrude came of age in, during the Lavender Scare when tens of thousands of gay people were purged from federal employment, and the post-9/11 New York that Dawn navigates over the course of the novel.

I didn’t think setting a book in the current moment would have the same impact as setting it in a time and place like 2003 New York, where we have enough distance to at least agree on certain facts. Regardless of the many varied opinions about how the 9/11 tragedy was handled, most people acknowledge that it inspired a staggering rise in hate crime, especially against the Islamic community, and led to increased government surveillance of everyday citizens.

But equally important, I find it inspiring to see how folks push back against oppression in oppressive times. As alluded to in Endpapers, during the Lavender Scare, small but powerful resistance movements formed and grew, such as the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society, gaining public attention for LGBTQ+ rights, and in the years following 9/11, even as George W. Bush was trying to amend the US Constitution to prevent gay marriage, it was on the cusp of being legalized here, in the state of Massachusetts.

NI: Bookbinding is the perfect profession for protagonist Dawn to discover the pulp fiction love letter quest that propels her to learn more about herself. Does bookbinding have a personal connection to you?

JSK: It does. I’ve always been fascinated by books as objects, as well as by paper and calligraphy and type. One year when I was kid, I got a Crayola calligraphy kit for Chanukah. I disappeared from the family party with it for hours! After college, I moved to Brooklyn and discovered the Center for Book Arts in Manhattan, and I got hooked immediately. I took workshops and sought out an internship at a local bindery, and that eventually led me to work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the book conversation lab of their research library. Since then, I’ve built up my own small bindery, which now resides in my basement. These days I don’t get much time to work in there, between writing, working full-time, and parenting. I still love it, however, and hope to return to it more seriously someday.

In Endpapers, Dawn is trying to figure out who she is—how to take pleasure in a body that seems to be at odds with her most of the time, how to get out from underneath other people’s perceptions of her and her body, and how to express herself from a place of confidence. The only way I’ve felt free to do this kind of self-exploration myself is through art. I wanted Dawn to be a book artist because books are a very special kind of art. They evoke intimacy (we take them into our most private places, including our beds), sensuality (we hold and interact with them), escape (we get lost in them), and authority (we turn to books for information and knowledge).

NI: As important to Dawn’s life as her romantic relationship is her friendship with best friend Jae. How did you decide how much of the story to dedicate to Dawn navigating these interpersonal relationships and how much to dedicate to her personal quest to find the author of the queer love letter?

JSK: In order to make Dawn’s quest feel important to the reader, I wanted to show a full picture of her life, to illustrate what the stakes are for her, whether they’re real or imagined. Ultimately, Endpapers is Dawn’s story so all of her interpersonal relationships feel as crucial to me as her search for Gertrude’s letter.

When it comes to Jae, his friendship with Dawn has been central to me from the beginning. I wanted Dawn to have a relationship outside her boyfriend Lukas, to create a contrast between how she feels around someone who seems comfortable with who she is and someone who calls it all into question. Also, while Dawn is genderqueer and bisexual, Jae is biracial, and I like to think that, even though they never discuss it outright, it leads to some understanding between them — of what it’s like to not fit neatly into any one community. Finally, Dawn is a difficult character. She’s messy and self-absorbed and leads with her impulses. Whereas Jae tends toward calm and stability, which is grounding for Dawn. But when he gets injured, of course that balance gets thrown off, and Dawn has to deal with that. She also has to learn that her friend does indeed struggle with his own challenges and has his own needs, even though he doesn’t usually express them. And this gives her a chance to be there for him — or at least try to. It’s a real growth opportunity for Dawn, which is something she needs.

Endpapers by Jennifer Savran Kelly (Algonquin Books, 9781643751849, Hardcover Fiction, $27) On Sale: 2/7/2023.

Find out more about the author at jennifersavrankelly.com.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.