An Indies Introduce Q&A With Caroline Brooks DuBois

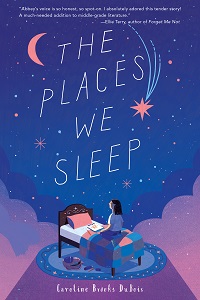

Caroline Brooks DuBois is the author of The Places We Sleep (Holiday House), a Summer/Fall 2020 Indies Introduce debut middle grade selection and a Summer 2020 Kids’ Indie Next List pick.

Caroline Brooks DuBois is the author of The Places We Sleep (Holiday House), a Summer/Fall 2020 Indies Introduce debut middle grade selection and a Summer 2020 Kids’ Indie Next List pick.

“The Places We Sleep is a beautiful and moving novel in verse about a girl navigating her way toward adolescence in the midst of a national tragedy,” said Chelsea Bauer of Union Avenue Books in Knoxville, Tennessee, who served on the panel of booksellers that chose DuBois’ debut for Indies Introduce.

“Abbey has just moved to Tennessee and is trying to find her way in a new school when the attacks of 9/11 happen. We follow Abbey as she deals with the fallout of 9/11 and the loss of the feeling of security the entire country felt. She grieves for an aunt, worries for her deployed father, and witnesses the xenophobia that reared its ugly head in the wake of that tragedy. If you are an adult, you’ll be transported back to that strange, unreal time. If you are younger, it will give you an idea of what it was like during those uncertain times. Either way, you will fall in love with and root for Abbey,” said Bauer.

DuBois holds a master of fine arts in poetry from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and has taught various poetry, writing, and English classes at middle school, high school, and college levels. She is currently a literacy instructional coach in Nashville, Tennessee.

Here, Bauer and DuBois discuss the author’s choice to write a novel in verse for middle grade readers that covers the events and fallout of September 11, 2001.

Chelsea Bauer: Abbey is such a great example of a kid with a parent or parents in the military. Did you pull from real life for inspiration? Were you an Army kid?

Caroline Brooks DuBois: Although I did not grow up in a military family, both my grandfathers served in the military, as well as both my brothers, my brother-in-law, and my sister-in-law. Abbey’s story is about being a military child, but it’s also about many other things — identity, loss and grief, creating art in the face of tragedy, tolerance and acceptance, and friendship. It’s about how world events can touch individuals in large and small ways. One area in which I pulled from real life for inspiration involves being the new kid in a school; I moved schools at a momentous time in my youth and recall those all-eyes-on-me moments with clarity. Likewise, as a teacher, I often witness new students coming into school and trying to acclimate socially and emotionally. I think many young people have felt like an outsider at some point and will relate to Abbey in this way.

CB: This book does a remarkable job of portraying the confusing and terrible weeks after the attacks on 9/11. What made you want to write about 9/11 specifically for an audience that was not around to experience it?

CBD: September 11, 2001, lives vividly in my mind, as it likely does for most people who lived through it. I consider it a lifetime impact moment, like John F. Kennedy’s assassination for my parents, or the Challenger explosion of my youth. It’s one of those moments where you know exactly where you were, what you were doing, and maybe even who you were with when you found out about it or witnessed it. My own children have now lived through at least three of these: Nashville’s historic 100-year flood in 2010; the March 3, 2020, EF4 tornado that hit our neighborhood; and now the COVID-19 pandemic. Wow, right!?

Every year when 9/11 comes around, I stand in front of my classroom hoping to teach the topic with integrity — details, facts, and emotions intact — but I always feel like I fall short. I felt inspired to tell a story for a young audience because they often have only a fuzzy understanding of the events of 9/11, and the nonfiction texts students typically enjoy the most in my classroom are almost always couched in a narrative story. For my high schoolers, we sometimes read The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation (Jacobson and Colón). Their eyes would widen when I told them we were going to read a graphic novel, and when we dug into it, they quickly realized how complex it was. With my middle-schoolers, I often watched the film Man in Red Bandana and read the poem “The Names” by Billy Collins. Still, I wanted to portray this moment in my own way, hence The Places We Sleep.

Stories can be visited and revisited and often bring hope in challenging times. I’ve seen a student have such a profound epiphany that they have an out-loud “ah ha” moment right in the middle of instruction. I love how fiction and poetry can inspire expressions of compassion and understanding and build bridges between students.

CB: Why did you choose to write this in verse?

CBD: Pregnant when 9/11 occurred, I feared bringing a child into such a frightening and unpredictable world. In the many years that followed, my brothers and my brother-in-law were all called into active duty and deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq. These events inspired Abbey’s story. I wanted to write about how world events have rippling effects on young individuals and their familial relationships in unexpected ways. Abbey’s coming-of-age story unfolded naturally in poetry, perhaps as a lyrical way to process 9/11, but also likely because I’d recently completed my MFA in poetry.

Poems can create powerful storytelling through their language and use of imagery, capturing the attention of a young reader verbally and visually. A poem can come alive in one way on the page and in another way when read aloud. Abbey’s story came to me with each poem as a scene or snapshot.

I think of writing mostly as pure creation and communication, but it definitely has therapeutic value, too, especially journaling. Each poem I wrote after the weeks and months following September 11 helped me to cope with the stress of the times. Being creative can battle one’s sense of helplessness in the face of things we cannot control. And writing is something anyone can do daily as long as they have pencil and paper or a device. Writing allows you the space to think, be present, persuade, inform, teach, inspire, or just share.

CB: Relationships are an integral part of this book and are portrayed in such a realistic way. Abbey behaves very differently while interacting with the various people in her life. Which relationship did you enjoy writing the most? Which one do you think was the most important?

CBD: That’s a complicated question. Camille, Abbey’s newfound best friend, would be the obvious choice, since Abbey fears losing this special relationship. However, I really enjoyed exploring what some readers might consider a secondary character, Jiman. When I look back on my youth, it’s often those “secondary characters” in my life who loom large and provocative. I’ve found that they are the ones who sometimes haunt or revisit me — the ones I could’ve been closer to, or the ones I might have loved if I would’ve been courageous enough to reach out and connect. That is Jiman in The Places We Sleep. Long story short, Jiman is the character I really enjoyed writing but also struggled with writing. Luckily, I had an astute editor and a sensitivity reader to guide me in my portrait of a character experiencing Islamophobia in the South after 9/11. I knew better than to overwrite Jiman, as if I’d lived her experience, and I knew I couldn’t underwrite her either. So I tried to give authenticity to Abbey’s point of view of a friendship on the verge, a friendship with potential, because I felt like that was the most honest portrayal. This budding friendship also has the most to do with Abbey’s personal growth in the story and the reason Abbey is simultaneously an unfinished character. She is still becoming who she wants to be.

CB: Abbey finds solace in her artwork as she struggles with her father’s deployment, her aunt’s disappearance, and her mother’s heartbreak. What would you say to readers about the importance of art during times of confusion and sadness?

CBD: Art has the power to provoke, to create change, and to bring people together and to help heal — I could probably expound here, but I’ll spare you. I’ve seen my own children process difficult moments in their lives by making art. The act of creating, in general, whether through art, writing, music, dance, acting, or other forms, is much healthier than the various forms of destroying or consuming with which people can become preoccupied. Adults in our world could probably take note from the innovative ways in which children cope. Creating art during times of trauma can help children deal with such events in a safe space, just as reading stories that act as mirrors and windows can. Maybe Abbey’s story will inspire some young reader to choose to deal with life’s challenges through art or poetry or other forms of creativity. I hope Abbey’s story will spark curiosity in young readers about 9/11 and the monumental lessons we learned and are still learning from that tragedy. Readers may witness how Abbey and her family coped, and they may find the courage and strength to cope with their own challenging times.

The Places We Sleep by Caroline Brooks DuBois (Holiday House, 9780823444212, Hardcover Middle Grade, $16.99) On Sale Date: 8/25/2020.

Find out more about the author at carolineduboiswrites.com.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions.