- Categories:

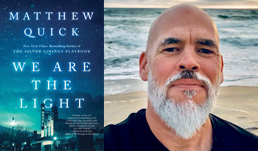

A Q&A With Matthew Quick, Author of November Indie Next List Top Pick “We Are The Light”

Independent booksellers across the country have chosen Matthew Quick's We Are The Light (Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster) as their top pick for the November 2022 Indie Next List.

Independent booksellers across the country have chosen Matthew Quick's We Are The Light (Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster) as their top pick for the November 2022 Indie Next List.

“Matthew Quick scores a perfect 10 in this deeply stirring, gorgeously hopeful novel that shines a brilliant beam on the path out of grief and toward healing,” said Beth Stroh of Viewpoint Books in Columbus, Indiana. “May we all learn the way to be such lights from this remarkable guide.”

Here, Quick discusses his writing process with Bookselling This Week.

Bookselling This Week: Thank you for this book and for finding your way through darkness to write it. Thank you for the light that came with the good cry I fought page after page and finally succumbed to, in a mix of tears and laughter brought only by pages filled with true vulnerability. Can you talk a bit about your journey from darkness to light that brought us We Are The Light, and your choice to share such vulnerability through the novel?

Matthew Quick: Glad you connected with WATL. Thanks for sharing that with me. Means a lot.

In June of 2018, I ceased drinking alcohol. I had been flirting with sobriety for a long time, but hadn’t previously been able to go all the way. What I learned in the following four-plus sober years is that — for most of my adult life — I had been abusing alcohol to numb parts of myself that were in tremendous amounts of pain. When I finally stopped drinking, all of those hurt places started screaming again.

My protagonist, Lucas Goodgame, doesn’t have a substance abuse problem, but he does numb his pain in other ways — primarily through the fantastical stories he tells himself.

For most of my writing career I was fond of saying, “Never trust a fiction writer who doesn’t drink.” And then I became one, which was disorienting to say the least. For a few years, my life got really small. In an effort to protect my sobriety, I pulled away from many people with whom I formerly drank. Sober me had a hard time doing much of what I used to do while drinking — social gatherings, writing fiction, watching sports, playing cards. I started running obsessively and lost a lot of weight. But I wasn’t taking on the necessary emotional and inner work. That didn’t happen until my Jungian analyst started challenging a lot of the stories that I had been telling myself for the first four-and-a-half decades of my life.

In many ways, my analyst shined a light on much of what I had previously kept in darkness — all of the reasons for those broken parts within me. And I had to start letting go of my defenses. During this time, my analyst often said I was in a chrysalis. I felt incredibly vulnerable. But then I began to slowly mend. It was the light — or truth — that brought me back to reality and gave me a sense that healing might be possible after all. And — symbolically — that’s exactly what WATL is about.

BTW: We Are The Light doesn’t shy away from the absurdity of life. Instead, it faces the absurdity of life head on. Through movie theater, screenplay, and film production references, the novel offers readers the opportunity to reflect on the way life is like a stage, one we each play a part in. What led you to include a film production in the storyline of the book?

MQ: Humans tell and listen to stories because stories are symbolic representations of our inner psychological problems. We yearn to understand ourselves and the human condition. And the Jungian analysis I’ve been doing has taught me that the ability to understand and consciously choose our own personal narratives is essential for our mental health.

At the beginning of the novel, Lucas has already experienced so much tragedy that his mind has fractured. In order to keep him from going totally insane, his psyche comes up with an absurd but medicinal — and maybe even beautiful — explanation for what is going on in his life. It’s a story he can live with for a time, while his heart and soul heal.

But part of getting better spiritually and psychologically is consciously taking control of — or reclaiming — our life’s narrative. I think that’s where the film production comes in, as well as the humor. The community offers Lucas a chance live out his fantastical narratives in a safe and loving container. The townspeople of Majestic gently hold his absurd notions, until he is ready to let go of the need for absurdity.

I fell in love with novels and began experimenting with story when I was a lonely, hurting teenager. Much of my adult life has been spent experimenting with absurd narratives. I have found this to be therapeutic. Soul medicine, if you will.

Lucas, Eli, and the entire town of Majestic, PA are very much in need of soul medicine.

BTW: We Are the Light touches on the idea of madness. The grieving process of the protagonist, Lucas Goodgame, speaks to the labels that come when someone cannot contain themselves within the margins of social expectations, and norms that cannot contain the margins of someone’s grief. Weaved within this complexity, We Are The Light offers readers a way forward, a way to make meaning of pain. As an intuitive creator, how did you bring the protagonist, Lucas Goodgame, to life?

MQ: Being an intuitive creator means living with the knowledge that I do not fully know how or why I am doing what I do when I write fiction. After not being able to write for many years, I just suddenly started writing WATL one day and couldn’t stop for a month. In many ways, it felt like channeling — or maybe as though something was writing through me. Is that a form of madness? Maybe.

Whenever I write, I need to be able to feel my way into the story. I have many times tried to map out story arcs and build preliminary character sketches, but none of that ever works for me. Once I feel my way into a voice or a character’s psyche, my mind makes connections very quickly and sometimes I will have a hard time keeping up with the flow of information that wants to jump from my brain to the keyboard. I’ve always privately felt a bit like someone who “cannot contain themselves within the margins of social expectations” and writing about those feelings has largely fueled my fiction writing career.

Perhaps there is a bit of madness in much of what we call the creative process? I’ve certainly experienced it that way. ‘Fiction writer’ is one of the few jobs that offers a paycheck in exchange for access to the fantasies of a novelist’s mind. But that’s not why I started writing and it’s not why I write now. For me, fiction writing continues to be a way to make meaning out of pain. I was in a lot of pain at the start of this latest creative journey. And the writing helped. When I began writing WATL, I didn’t know if the idea was marketable or even publishable, I just knew I had to write it.

BTW: Your ability to share, through fiction, truths about how our minds protect us from what we aren’t ready to handle, is admirable. In your “Letter From The Author” and in your Acknowledgements, you share your recent journey as a writer experiencing writer’s block. For the writers and future writers inspired by your work, can you share your experience with writer’s block? Do you think writer’s block is at times a way for our minds to protect us from what we aren’t ready to handle?

MQ: For most of my adult life I dealt with my anxiety and depression by writing and drinking. Perhaps ironically, my great big getting-sober reward was crippling writer’s block, which — for almost four years — kept me from getting anything worth sharing down on the page. At the time, it felt like the cruelest of punishments. Every single day I went to my writing desk and forced myself to type, but nothing good would come. There were many days when I sat for eight hours without producing a single sentence. Years went by where I barely produced ten pages — and those ten pages were terrible. I’d show them to my wife and she’d be frightened, because they were not even remotely publishable.

I had been talking openly about my anxiety and depression since I published The Silver Linings Playbook in 2008. I had been speaking up about mental health awareness. I often had encouraged others to get the help they needed. But my dark little secret was that I myself had never gotten the help that I needed. I drank and wrote. And that got me through my thirties. Things started to fall apart in my forties. My body began breaking down and it got harder and harder to pretend I didn’t need mental health assistance. Still, I pigheadedly tried to lone wolf it for as long as I could.

My analyst has suggested that my psyche shut down my ability to write as a last resort so that I would finally enter into analysis and begin healing. When I was in that raw vulnerable place of early sobriety, a book tour probably would have killed this introvert. And then the beginning stages of analysis required everything I had in me. It was by far the hardest thing I have done in my life. There were times when a session would end and I literally couldn’t get up out of the chair. I remember demanding — in fits of frustration — that my analyst tell me exactly when I’d be able to write again and he’d calmly say something like, “You have no control over this process. Let go. Surrender.”

Looking back, it is easy to see that I desperately needed a break from writing. My ego would never have allowed me to willingly take the necessary time off to deal with my physical and mental health problems. So psyche shut me down.

BTW: The characters of We Are The Light face tragedy, shared traumas, and generational wounds. The characters act with courage, empathy, patience, and humility, and together embark on a collective healing journey through art. Why was it important for you to create a community of survivors who heal through art in the novel?

MQ: Again, I tried the lone-wolf method — especially when I first got sober — and it took me to a very dark place. My wife and a few close friends really stood by me and — from time to time — forced me out of my hermit-like existence. Looking back now, I can see how vital these simple interactions were. Lunch once a week with my OBX buddy, Matt; swimming on Sundays and playing kubb with my friend Adam; daily meals and walks with my wife; Saturday morning phone calls with my brother; movie club with my friend, Kent — all of these things kept me from getting too lost in the darkness of solitude.

About a year into my analysis, I started writing letters to old friends and telling them what I had been through in an effort to explain my sudden disappearance from their lives. Some of these people welcomed me back. Not too long after that, I began writing fiction again. I spoke monthly about my creative process with my friend, the novelist Nickolas Butler. Then my wife, Alicia, read the first draft and gave me incredible notes, which we used to revise and edit. My agent, Doug, read the book next and began sending it out into the world, which is how I met my intrepid and fiercely optimistic editor, Jofie Ferrari-Adler, who introduced me to the entire Avid Reader Press team. Then they sent the Advanced Reading Copies out to indie booksellers, with whom I started corresponding in various ways. I was back in the book community’s loving arms.

In late September of 2022, I flew to Denver and spoke at the MPIBA FallCon. I talked about my sobriety and writer’s block and the hard battle I’d been through over the past five years. I discussed losing my community and how I had been and was still fighting hard to reenter. I talked about WATL and the need for positive masculinity to defeat toxic masculinity. I talked about my belief that art and story really can heal us. When I sat back down and reached for a glass of water, I noticed that my right hand was shaking. It was the first time I had spoken in person and in front of a live audience since I had gotten sober.

After the other writers had given their talks and the panel was over, several booksellers approached me. Each shared a little bit about their own personal struggles. I was touched by their sincerity. I felt supported and understood.

When I made it to the display floor, the room was teeming with booksellers who were eager to find the soul medicine that their communities needed. And I thought to myself, this is what my latest novel is about. Art and community. People supporting each other. And as I interacted with the booksellers in the room, I experienced an abundance of courage, empathy, patience, and humility.

Sometimes when I look at social media or the news or elsewhere, I can be tricked into thinking that there is a scarcity of courage, empathy, patience, and humility in the world. But there’s not. Maybe we are just too often pointing the cameras at the wrong things. WATL is my humble attempt to draw some attention back toward the right things.

BTW: For the letter writers and letter lovers amongst your readers, We Are The Light is a special treat. Lucas’s letters to Karl offer a window into the intimate thoughts and feelings Lucas processes through the book. The letters offer a raw and truthful account of the impact of soul connections, what it means to need someone, and what it means to be a part of a community. The letters remind us to see and love the best parts of each other. What inspired you to write We Are the Light through a series of letters?

MQ: When I was blocked and couldn’t write fiction, Alicia pointed out that I could still easily write letters. I have always had pen pals and enjoy writing handwritten notes to friends and loved ones. Without even knowing that Alicia had already recommended it, Nick Butler also suggested that I try writing another epistolary novel. To be honest, I didn’t want to. But when I finally sat down at the computer and wrote the words, “Dear Karl,” I was off.

Back in 2002, when I was still a high-school teacher, I chaperoned a trip to the Peruvian Amazon jungle. Our riverboat guide was an ex-pat named Scott. One late evening over beers, I opened up and told Scott I wanted to be a novelist. He said, “Leap and the net will appear.” Even though he was almost my father’s age, Scott and I became fast friends and when I returned home, we began emailing several times a week, a correspondence which continued, uninterrupted, for just about two decades. For reasons I didn’t understand at the time, Scott’s emails dramatically slowed in 2020. In January of 2021, I learned that Scott had passed away in the jungle town of Iquitos after hiding a series of strokes from his friends and spending the last months of his life alone in his home. Just about seven or so months later, the writing of my epistolary novel really took off. I’m actually just making that connection right now. I really missed my pen pal.

I believe that letter writing is a tragically lost art. If you have ever received or written a long heartfelt letter, then you know the intense feeling of intimacy such a note can invoke. Lucas Goodgame is craving intimacy throughout the novel. And being intimate on the page saves him. That’s also saved me a million times and counting.