- Categories:

An Indies Introduce Q&A With Joseph Han

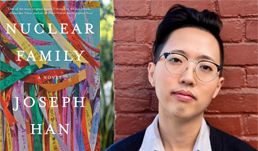

Joseph Han is the author of Nuclear Family, a Summer/Fall 2022 Indies Introduce adult selection, and June 2022 Indie Next List pick.

Joseph Han is the author of Nuclear Family, a Summer/Fall 2022 Indies Introduce adult selection, and June 2022 Indie Next List pick.

Han was born in Seoul, South Korea and raised in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. He is a 2022 National Book Foundation 5 under 35 Honoree. and an Editor for the West region of Joyland Magazine. His writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Nat. Brut, Catapult, Pleiades Magazine, Platypus Press Shorts, and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. A recipient of a Kundiman Fellowship in Fiction, he received a PhD in English and Creative Writing at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where he taught Asian American literature, fiction workshops, and composition.

Jonathan Hawpe of Carmichael’s Bookstore in Louisville, Kentucky served on the panel that selected Nuclear Family for Indies Introduce. Hawpe said of Han and his debut, “Joseph Han crashes onto the literary scene with this wildly original magical realist/political satire/family comedy that piles together a stoner gal in Hawaiʻi, her straight-arrow brother, cranky deli-owner parents, and the spirit of their dead Korean grandfather on an afterlife mission of cultural healing. Smart, funny, sad, bawdy, sweet and sour; if this book were pizza it would be a hot, delicious ham and pineapple.”

Here, Han and Hawpe discuss Nuclear Family.

Jonathan Hawpe: What role did your own background play in writing a story set in Hawaiʻi and Korea, centering on a multi-generational family of immigrants, all with their own varied ideas and identities?

Joseph Han: I was born in South Korea and raised in Hawaiʻi after immigrating with my grandparents, while my parents stayed behind. Eventually my parents joined me with my younger sister. It’s the many years we’ve spent apart that influenced my understanding of how separations reverberate across the Korean peninsula and the Korean diaspora. Many older generation Koreans still cannot see their families in North Korea since armistice — though the war lives on. My novel also reflects my own coming into awareness, as a Korean settler on Hawaiian land, of Korea and Hawaiʻi’s entangled histories of US occupation and militarization. As Iʻve seen how people have described the Cho family, and myself, it bears repeating that living in Hawaiʻi does not make one Hawaiian!

Though I hardly lived in a traditional nuclear family, it was something I always wanted. To live with my immediate family together in a house. The novel reflects this desire, how strong a bond and bind the nuclear family unit can be, the way it’s propped up as an ideal, heteropatriarchal framework that governs our aspirations to struggle under capitalism, acquire property, all for the sake of protecting our own and in the name of progress. But our understanding of family needs to be capacious and include connections across many divisions, as we are becoming more detached from our relationship and responsibility to land.

When the novel talks about hopes for peace, that one day the Korean DMZ no longer divides the peninsula, it is also talking about Hawaiian sovereignty and how the US military must return the lands where they train for and practice war. What stories and genealogies must we re-tell and remember? Kanaka Maoli have ancestral ties and rights to land, where ʻāina is an ancestor that must be respected and nurtured. Meanwhile, the rest of us have benefitted from being on Hawaiian land, viewing Hawaiʻi as an occasion for a tourist fling, which risks disregarding the everyday violence, desecration, and pollution that the US military brings to Hawaiʻi and across the globe as the largest threat to the planet and all its lifeforms.

Jonathan Hawpe: Humor seems to be an important ingredient in Nuclear Family even though it's a story with plenty of gravitas. What led you to include so much levity, and what kind of creative decisions did you make to achieve the right balance?

Joseph Han: I’d like to think the balance came naturally, in the way comedy and tragedy have a greater resonance when they contain one another. There is so much to bear and hold when it comes to Korean history and the ongoing war. I thought about the reader’s journey when it came to knowing that I also needed to write and experience moments of levity if I were to survive this undertaking of writing the Korean DMZ, and feeling it deeply, while offering the hope of healing.

I thought a lot about the saying, how we need to laugh so we don’t cry. There’s always a brief moment where I notice that while I’m weeping it almost sounds like laughter; and likewise, when something is incredibly funny, we have this capacity to laugh ourselves to tears. Sometimes our responses are so strong that we can laugh or cry without sound, where we then need to retrieve and regulate our breathing. Matthew Salesses describes pacing as a modulation of breath and how we transmit information. Laughter can be very specific, begging the question who’s in on the joke, who will laugh more deeply and harder. The same goes for crying. This kind of oscillation was central to the way I moved through the book, and how I hoped the book would move specific readers and readers broadly.

Jonathan Hawpe: The conception of an afterlife in Nuclear Family is unconventional and surprising. What influences and/or motivations did you have in creating this element of the story?

Joseph Han: The epigraph in my novel comes from Nora Okja Keller’s novel Comfort Woman, one of the first Korean American authors I’ve read. The imagery in those lines suggested to me that the Korean DMZ has a greater impact beyond what we can perceive. That book unlocked my whole world and imagination, compelling me to learn about the history of Korea’s division and my own family’s place in it. Currently, the generation directly impacted by the division is passing, still carrying their wish to see their relatives in North Korea, to return home. I worry their will and desire will be lost if it’s not carried on by the living. Jacob learns this the hard way, and with resistance, but eventually he understands why his grandfather will stop at nothing to get to the other side. I’m working on an essay on this, so that’s it for now!

Jonathan Hawpe: Nuclear Family includes characters and situations that can be described as both fantastical and naturalistic. How did concepts like “realism” and “stylization,” or perhaps tropes and genre, play into your writing process?

Joseph Han: Since my book is so much about boundaries and attempting to break through them, Tae-woo’s resolve likewise possessed me as a writer, and I was inspired to push genre boundaries beyond my own limits, taking as many attempts and failures as possible. This was my first time writing in all these different registers, and various chapters take on different perspectives and tones. As a novel about a plate lunch restaurant, I found it appropriate to serve a bit of everything all in one place.

Jonathan Hawpe: Nuclear Family is full of people having a hard time finding a path in life, or being haunted by the past. This seems both universal, and perhaps particular to families connected to socio-political ruptures such as the Korean War. How do you weigh telling a story that resonates broadly against one that feels uniquely personal?

Joseph Han: I think what’s uniquely personal about this book, and the reason why it can resonate broadly, is that I am writing in a language that has eluded me from my history, and yet I am writing to return. It is the language of the country that taught me to believe the war and violence they brought, the absolute devastation they caused on the Korean peninsula, and its ongoing division, continues to be just. These are characters who are living in a world where, when one speaks about Korea, they are mostly referring to South Korea and not its entirety. I write and live to speak back, against forgetting.

And so, it is through the personal that we create and redefine the language of our lives, the way we live and move through the world, to articulate why a seemingly universal story [of] family separation — missing someone you love, reuniting after lifetimes — is tragically particular to Koreans and our history of war, and why our healing is obstructed. What is universal is how wildly accepted our militarized realities are, and I hope this novel inspires the understanding that demilitarization and peace is the path to a livable planet for us all.

Nuclear Family by Joseph Han (Counterpoint Press, 9781640094864, Hardcover Fiction, $26) On Sale Date: 6/7/2022

Find out more about the author at joseph-han.com.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.

For clarity, full names were used to label this interview.