- Categories:

Wi13 Keynote Speaker Junot Díaz on Writing His First Book for Children

- By Liz Button

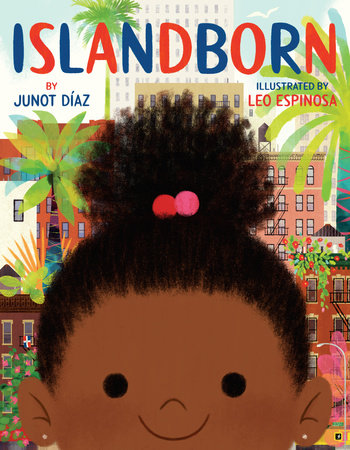

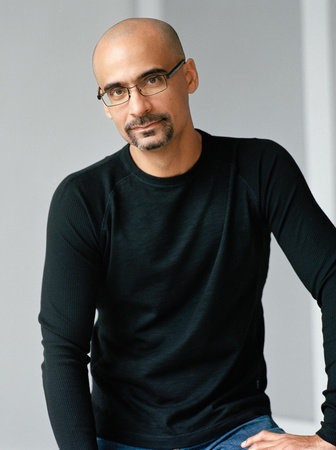

Junot Díaz, whose first children’s picture book, Islandborn, will be published on March 13, 2018, by Penguin Young Readers, is set to appear as a keynote speaker at the American Booksellers Association’s 2018 Winter Institute in Memphis this month.

Islandborn, illustrated by award-winning Colombian artist Leo Espinosa, tells the story of a young girl from the Bronx named Lola, whose teacher asks the class to draw the place where they are from. Lola, however, left the Dominican Republican as a baby, and can’t remember her former home. As Lola searches the collective memory of her family, friends, and neighbors for clues about the island, the book’s vibrant illustrations show how Lola uses her imagination to come up with her own conception of home.

Díaz, who was born in the Dominican Republic and raised in New Jersey, is the author of the critically acclaimed Drown; The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, which won the 2008 Pulitzer Prize; and This Is How You Lose Her, a New York Times bestseller and National Book Award finalist. Díaz is currently the fiction editor at Boston Review and the Rudge and teaches writing at MIT.

Díaz will speak from 7:45 a.m. to 9:00 a.m. on Wednesday, January 24, in Ballroom A&B at the Memphis Cook Convention Center, where ABA’s 13th annual Winter Institute will take place from January 22–25, 2018.

Bookselling This Week recently spoke with Díaz about his first time writing for children, how immigrant families deal with their painful pasts, and how booksellers can encourage diversity in their stores.

Junot Díaz: I wanted to write a book for my godchildren — young people from immigrant backgrounds who don’t always remember the lands they left. That was the first impulse above all others: To give my godchildren something to enjoy, a book that addressed them and their experiences directly, with sympathy and, hopefully, nuance. It was an act of love more than anything: love for my godchildren and love for the immigrant communities that give so much to all the countries they find themselves in. Of course, the past year’s xenophobic eruptions have made such acts of love nearly revolutionary. We’re living in a time where stories about immigrants and immigration are being framed primarily by people who hate us.

But to return to your question, I was one of those young immigrants who was keenly aware that there was some hidden backstory to my parents’ departure from the Dominican Republic. Even before I knew about the Trujillo dictatorship and all its predations, I sensed it in the care with which my parents talked about their past, in the silences they seemed to nurture. It took me a while to find out the truth behind the silences. In the lead-up to Islandborn, I wondered if it was possible to approach that experience — the unraveling of our family’s national silences, which is often a central “plot” of a lot of adult immigrant narratives — but to do so in a way that would resonate with children. When I was young, my parents rebuffed all my questions about our past, but it’s a new age and many of my generation have a different parenting ethos. Now, when a girl like Lola (my protagonist) becomes curious about her family’s history, there’s a good chance she might get useful answers.

BTW: A children’s picture book is a departure from your typical writing. What was the process like collaborating with an illustrator? What was it like writing and publishing a book for kids for the first time?

JD: I loved working with Leo Espinosa. To be frank, I think I’d gotten incredibly tired of working alone all those years, so the process of collaboration was a welcome thrill. And, as I’m sure you know, sometimes these things just don’t work out. My first crack at it with Leo was blessedly easy and generative. He’s from Colombia, a Caribbean nation, and he’s an immigrant, so we had a lot of common ground between us. And then there’s the fact that he draws like a dream.

What’s been the most interesting part about publishing a picture book has been getting to know this entire other literary world that I knew nothing about — this is a world with its own codes, hierarchies, preoccupations, history, and passion like I never imagined.

BTW: Islandborn features diverse schoolchildren of many different nationalities. Do you have any advice for booksellers who are looking to get more diverse books, staff, and clientele into their stores?

JD: Few are the fields, businesses, institutions that don’t have a problem with diversity. Literary culture certainly isn’t immune. Now, I understand that each context is unique and requires experimentation, but what has always seemed to work is making diversity/equity a central mission and not some fleeting whim. If diversity is a problem and you don’t feel like you’ve got enough resources to change things, assemble an advisory board of volunteers from the community to help make it happen. Meet once a month; see where that can take you. Enlist every available means to help make the enfranchisement of underserved literary communities a reality. You have to be like a writer: try everything, make a lot of mistakes, until you figure out what works for your specific situation. The worst position is to think you’re doing great. I’ve seen that a number of times — folks think that their intentions count for more than their practice. When you think you’re doing great, versus always wanting to do better, that’s more likely than not when you’re not serving your community as well as you could.

BTW: The monster in Islandborn is never named, but one can guess it represents dictator Rafael Trujillo, who terrorized the populace of the Dominican Republic from the 1930s until he was assassinated in 1961. Did you leave the specific history of Trujillo out of the book so that parents have a choice whether to explain the metaphor to their children?

JD: Many of the immigrant communities I grew up with emigrated from histories of violence, of dictatorship, of conflict. When we were children, our parents often hid these histories from us, and yet we kids sensed that there was a secret, a trauma, a sadness, a silence that had followed us from our home countries. We could intuit that monsters lurked over our lives, but we wouldn’t learn the exact nature of them until we were adults. For immigrant kids, the monster is often not in our closet or under our bed but looming over the countries we left behind, hiding behind the stories our parents do not tell. With Islandborn, I hope to remind young people how normal it is to have a monster in our family history and, in doing so, offer up a space where these monsters can be worked through, if parents and children so wish.

BTW: What role have indie bookstores played in your life? Will you be touring and visiting many for Islandborn?

JD: Sadly, I grew up in something of a bookstore desert. When you grow up poor and marginalized spatially, that is often the case. There weren’t bookstores of any kind anywhere near our neighborhood. I had to ride a bus over an hour to reach a Waldenbooks (back when there were Waldenbooks). It wasn’t until I was older and had a car that things changed. I found the Montclair Book Center, among other places, a bookstore I still visit regularly.

But to speak strictly as a writer, I wouldn’t be where I am if not for independent bookstores. My first book, Drown, stayed alive, and in turn kept my career alive, because independent booksellers continued to put the book in people’s hands long after everyone else had forgotten it. For 11 years, I had no other book and yet indie booksellers kept their faith in me. To them, I owe very much. I’ll definitely be in a lot of indie bookstores on this tour, as many as will have me.

Díaz’s breakfast keynote will take place in Ballroom A&B at the Memphis Cook Convention Center from 7:45 a.m. to 9:00 a.m. on Wednesday, January 24.

Winter Institute 13 is made possible by the generous support of lead sponsor Ingram Content Group and from publishers large and small. See the full Winter Institute program here.