- Categories:

Jewell Parker Rhodes on Spring Kids’ Indie Next List Pick “Ghost Boys”

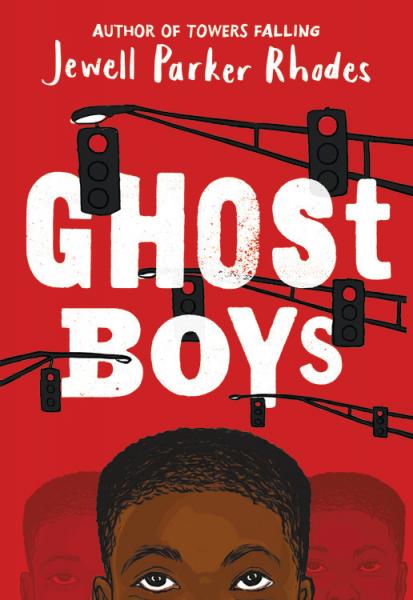

Independent booksellers across the nation have named Jewell Parker Rhodes’ Ghost Boys a top pick for the Spring 2018 Kids’ Indie Next List.

Available on April 17 from Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, Ghost Boys tells the story of 12-year-old Jerome, who is slain by a police officer while holding a toy gun. Jerome’s death is just the beginning of a novel that blends history and fiction to bring to life a child whose story doesn’t end with the sound of a gunshot. As narrator, Jerome’s ghost witnesses his family’s grief and anger and meets the spirit of Emmett Till, another black boy unjustly killed. Lending the novel optimism and hope for the future, Jerome is also able to communicate with, and even befriend, the daughter of the police officer who killed him, causing her to question why a boy her own age was seen as a threat.

Available on April 17 from Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, Ghost Boys tells the story of 12-year-old Jerome, who is slain by a police officer while holding a toy gun. Jerome’s death is just the beginning of a novel that blends history and fiction to bring to life a child whose story doesn’t end with the sound of a gunshot. As narrator, Jerome’s ghost witnesses his family’s grief and anger and meets the spirit of Emmett Till, another black boy unjustly killed. Lending the novel optimism and hope for the future, Jerome is also able to communicate with, and even befriend, the daughter of the police officer who killed him, causing her to question why a boy her own age was seen as a threat.

“Ghost Boys is a devastating novel, but it is also hopeful, full of compassion, and a compelling case for the fact that ‘we can all do better, be better, live better.’ Jerome’s story is heartbreaking, and the telling of it is necessary, just as the telling of Emmett Till’s story is necessary, though it so often goes untold,” said Michelle Cavalier of Cavalier House Books in Denham Springs, Louisiana. “Rhodes has crafted a beautiful novel that will facilitate many conversations with young people. Ghost Boys is essential for the middle school classroom as well as for family discussion. This is a novel to be shared with children; read it with them, discuss it with them, and together we can gain the tools we need in order to live better.”

Rhodes is the author of Ninth Ward, Sugar, Bayou Magic, and the 9/11-inspired Towers Falling, as well as a number of fiction and nonfiction titles for adults. She has received numerous honors, including the American Book Award, the National Endowment of the Arts Award in Fiction, the Black Caucus of the American Library Award for Literary Excellence, and more.

Here, Rhodes discusses the process of writing Ghost Boys, the blending of fact with fiction, and other contemporary titles for young readers that explore the Black Lives Matter movement.

Bookselling This Week: When did you get the idea for Ghost Boys?

Jewell Parker Rhodes: When my editor said, “What about the young black men dying?” I said, “Oh no, no.” I didn’t think I could do it. But I felt this strong calling, and I kept thinking about it, and how I would do it. It was thrilling to see whether I could become good enough to write the book. It was worth it to give to this generation of kids because they’ve given me so much in life, and I’m waiting for them to grow up and rule the world and make it a better place. I also started thinking about how I was born the year before Emmett Till was murdered. I remember the Ebony and Jet magazines and seeing the segregation, the civil rights images, and Martin Luther King on our television set with his “I Have a Dream” speech. My son was two years old when the Rodney King beating happened, and I wrote an essay about how my two-year-old who loves Legos could one day be terrified a police officer would beat him. Tamir Rice really hit me in my core. He was from Chicago, like Emmett Till. He was a 12-year-old boy. Emmett Till was 14 years old. If you’ve ever seen the video of the policemen pulling up to Tamir Rice, the car leaps over the curb, the police officer gets out of the car before it even stops, and fires. You think about tasers. What about warnings? What about “Stop, halt”? What about the fact that they let him lay there as he was bleeding and dying?

Jewell Parker Rhodes: When my editor said, “What about the young black men dying?” I said, “Oh no, no.” I didn’t think I could do it. But I felt this strong calling, and I kept thinking about it, and how I would do it. It was thrilling to see whether I could become good enough to write the book. It was worth it to give to this generation of kids because they’ve given me so much in life, and I’m waiting for them to grow up and rule the world and make it a better place. I also started thinking about how I was born the year before Emmett Till was murdered. I remember the Ebony and Jet magazines and seeing the segregation, the civil rights images, and Martin Luther King on our television set with his “I Have a Dream” speech. My son was two years old when the Rodney King beating happened, and I wrote an essay about how my two-year-old who loves Legos could one day be terrified a police officer would beat him. Tamir Rice really hit me in my core. He was from Chicago, like Emmett Till. He was a 12-year-old boy. Emmett Till was 14 years old. If you’ve ever seen the video of the policemen pulling up to Tamir Rice, the car leaps over the curb, the police officer gets out of the car before it even stops, and fires. You think about tasers. What about warnings? What about “Stop, halt”? What about the fact that they let him lay there as he was bleeding and dying?

BTW: There is a powerful moment in Ghost Boys when Sarah, the daughter of the policeman who killed Jerome, looks at him and realizes that they are the same age and size despite her father’s description of him as big and scary. What did you want to achieve with that connection?

JPR: I knew Sarah and Jerome were going to have this experience, and she was going to have an impact and she was going to bear witness for Jerome’s story. When you discover your parents aren’t perfect — that they can make mistakes, and they are horrible mistakes — but they are still your parents and you love them, that, to me, is connected to the moment when she realizes that she and Jerome are the same size, and emotionally there is no way to absolve her father. She has hard, concrete evidence in front of her that they are the same size and in the same grade, and that is when she starts becoming an individualized, thinking, critical person, and that’s what we want everyone to be. We hope to raise independent thinkers, and that is part of a rite of passage every kid has to make. She makes it in this particularly horrifying and tragic way, and yet that knowledge sets the stage for her to become a person who makes the world better.

BTW: Was the process of writing Ghost Boys different or similar to other novels you’ve written that blend fact and fiction?

JPR: I’ve never written a book the way that I’ve written this book. It came in fits and starts, and it broke my heart even to do the book. It did not come easy. I finished it in August, and I haven’t written anything since. I have had people tell me they think that I’ve gotten it right, but I’ve never had a book that caused me so much pain, that took so much time. I never wanted to go to work on the book, but I felt the calling to try to get it right because I’m so saddened by the era in which we live. Why do I get to be in my sixth decade, and having seen the civil rights movement, having seen so much happen, why are we going back to these racially charged times? It gave me an urgency to speak to the kids who are like Jerome and Sarah — forming, growing, and changing and becoming the citizens that will rule our world.

BTW: What gave you the idea for allowing Jerome to communicate with the daughter of the police officer who shot him?

JPR: I started my career steeped in my grandmother’s southern roots — hoodoo folk tale tradition. In the African American community, it’s believed the dead are never gone. From the time I was a little kid, talking about ghosts, dreaming about ancestors who were dead, and playing the numbers have been part of my cultural heritage. When I wrote Voodoo Dreams, I went to Louisiana, which had that same tradition. It’s all part of the African diaspora. I steeped myself in the African diaspora and the way in which African, African American, African Christian, hoodoo, Catholicism, all that blends and is at the root of a lot of religious traditions celebrated by black people all over the world. I’ve always believed in the power of the ancestors, that the dead are not gone, that they are still accessible. That’s a cultural tradition, and it’s linked to many other great cultures.

BTW: Sarah, with her dawning awareness of the injustice Jerome and other black boys and men experience and her determination to fight it, humanizes the family of the policeman. Why is her emotional and intellectual arc important to the book?

JPR: It’s part of the tradition of bearing witness, which is part of African American tradition and a lot of other traditions. The catharsis that comes from telling your story, the healing and the power of it, is very important in the African American heritage. Emmett bore witness to Thurgood Marshall. Thurgood Marshall becomes a great civil rights leader and Supreme Court justice. Jerome is able to bear witness to Sarah. That’s how Sarah’s life is forever changed, and she is going to carry forth activism in her life. She may be a lawyer, and Jerome can see her being a mom, or she could be a Supreme Court justice — who knows? Only the living can make the world better, and that’s Sarah. Her role is vital.

BTW: There have been several books published recently that explore the Black Lives Matter movement from a fictional perspective, including Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give (Balzer + Bray) and Dear Martin by Nic Stone (Crown Books for Young Readers). How do you feel your book fits into this effort to explore these themes?

JPR: My whole life got me ready to write Ghost Boys in the way that I wrote it. I could not have done it younger. There are differences in all of our books, and they are all needed. There are other 9/11 books coming out, and they are all needed. If you look at my canon that I’ve done so far, it is me bringing everything I did as an adult novelist — race, class, gender issues, the feminist movement, the civil rights movement — I bring all of that and try to give it all to kids, but in a way that is not patronizing, that is not cheating the process. If I wrote a book that a kid wouldn’t read in middle school, then it wouldn’t be art. I was meant to write this book. I really believe it.

BTW: What are you reading now? Are you working on another book that blends history and fiction?

JPR: The book I had on the plane with me was Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge [by Erica Armstrong Dunbar (Atria / 37 INK)]. I had never known this story. Clearly, I love history and historical fiction, but I read everything. I also do a lot of reading for novels I’m getting ready to work on. Right now, I’m reading a lot about fencing because I’m writing a book about fencing. Did you know that Alexandre Dumas was black? The guy who wrote The Three Musketeers was a black man. I discovered this when I was 19 years old. I’ve been waiting to write this book for a long time. Five years ago, a book came out about Alexandre Dumas’ father, who was a Napoléon’s finest general. It’s called The Black Count [by Tom Reiss (Crown)]. It’s believed now that Alexandre Dumas wrote all of his stories based on his father’s life, the great fencer and general. Fencing is known worldwide as an elite, white, aristocratic kind of sport, but Alexandre Dumas probably saw the Three Musketeers as black men. Why don’t black kids know that?

BTW: Booksellers named Ghost Boys a Kids’ Indie Next Great Read. What advice would you give to booksellers when it comes to hand-selling your book?

JPR: Though I was sad writing it, I don’t think this is a sad, sad book. Ultimately, Ghost Boys is about children empowering others to make the world better. My faith is with children. As adults, we think we know everything, but there is a lot we get wrong. This is my song, my story to give kids to tell them we are waiting to hear their words. It’s a love song to them. My gratitude to the booksellers is so deep because I know they are nothing but lovers of books, and they are going to be honest and critical, and they have a special responsibility in what books they are going to hand to a child. What better group of people to say, “OK, Jewell, we think you did good.”