- Categories:

An Indies Introduce Q&A With Andrew Forsthoefel

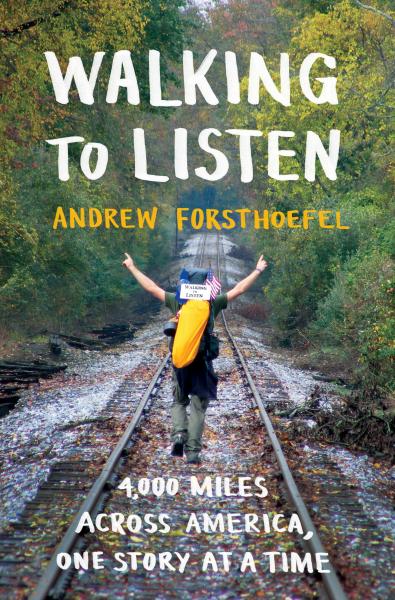

Andrew Forsthoefel is the author of the Winter/Spring 2017 Indies Introduce pick Walking to Listen: 4,000 Miles Across America, One Story at a Time (Bloomsbury).

Hilary Gustafson, co-owner of Literati Bookstore in Ann Arbor, Michigan, who served as an Indies Introduce Adult debut panelist, called Forsthoefel’s debut “a thoughtful and inspiring portrait of America today.”

“This book could not be coming at a better time. Amidst a calamitous political landscape, Americans today seem wary of their fellow citizens, suspicious of one another’s beliefs, religion, and ethnicity. Forsthoefel does an amazingly wonderful job showing us that our fellow citizens are not to be feared, but instead are to be celebrated for their humanity and their heart. The stories he brings us of the individuals he meets, in addition to his own personal journey, are insightful and ultimately uplifting,” said Gustafson.

Forsthoefel, who hails from the Pioneer Valley in Western Massachusetts, is a writer, speaker, and peace activist who spent 11 months walking across the U.S. collecting stories from everyone he met along the way.

Here, Gustafson and Forsthoefel discuss what he learned during his travels.

Hilary Gustafson: Trust seems to be a fundamental exchange throughout your journey on the road. You trust those who offer help, companionship, a meal, their time. Those people trust you enough to invite you into their homes and to offer up their time and to tell their stories. What did you learn about trust?

Andrew Forsthoefel: I found that when I trusted people unconditionally — without the expectation that they would or should reciprocate my trust — it seemed to have the paradoxical effect of making them want to be worthy of such a vulnerable, powerful gift. Trust, earnestly and radically given, seemed to beget trustworthiness. I was, on my good days, sincere — not cynical or paranoid — speaking from a place of humility, of recognizing that I did not know the whole story, that I needed help in understanding myself, and my country, and my people. I looked at people in this way, as if they were worthy of my time and attention, as if they might have lived something that could be a needed contribution to the collective conversation about how to live a responsible, beautiful life. Speaking to people in this way had the effect of inviting out their intrinsic goodness, or nudging them to realize their capacity for goodness. Think about it: When someone asks you an earnest question — free of artifice, pretension, and agenda, from the depths of their own personal struggle, without judgment, open and undefended — it would be hard to slap that person in the face, right? Take their lunch money? Shoot them, stab them, weaponize your language against them? That is the alchemical power of trust: When I look down at you from on top of a ledge and say, “I trust you completely,” and then close my eyes and fall backward, you’re probably going to do what you can to catch me. Doing nothing, or actively contributing to harming me, would force you to confront some challenging questions about yourself the next time you looked into a mirror.

Not that there is a foolproof formula to this dynamic. There was never a guarantee that I would not get hurt, manipulated, or betrayed by the people I was able to trust. And that’s what made it such a powerful expression of love. I chose to trust, even when I had, it sometimes seemed, every reason not to. However, the more I trusted, and the more I experienced what’s possible when trust is at the foundation of a relationship, the clearer it became that there were more reasons to trust people than to not trust them. A whole other universe suddenly became accessible, in which deep connection with anyone was possible, the kind of connection that cannot come to fruition without trust, and the respect for someone’s fundamental, non-negotiable, irrevocable worthiness that trust implies. “You are worthy of my breakable heart,” the trusting one says to the trusted, “whether you choose to break it or not.” That’s intense, right? For both parties involved.

Eventually the cost of not trusting — of fearing, living in a world where everything was curbed, edited, hedged, hamstrung, and choked by fear, in little ways and big ways — became greater than the potential cost of getting hurt if I trusted. If I got hurt, I could at least know that I was engaged in the work of midwifing into reality a new world of love, in my own tiny way, and that my hurt was a part of the price we all had to pay to bring it into being. That world can only come if we are willing to start living it. And yes, it is scary. But maybe it’s actually much scarier to live in this world — fearful, paranoid, possessive, violent — and we are just used to it, numb to how much it actually hurts to be afraid of each other all the time, and of ourselves.

HG: Food plays a major role in your connections on the road. What did sharing a meal with someone mean to you then? Did it change the way you viewed your everyday experience of sitting down to eat?

AF: On the road, I was acutely aware of how dependent I was as a human being — constantly and unavoidably dependent, upon the earth, all the elements, people. If it rained, I got wet. If it was hot, I got burned and sweaty and dehydrated. If I was alone, I might feel lonely. I was of my environment in a way that I never had been before … or perhaps just more aware that I was, always had been, and always would be of my environment. What does this mean? It means I am affected by everything that happens in the world, connected to it in obvious ways, subtle ways, and mostly invisible ways that are no less real just because I can’t see them. In cars, in buildings, in the often numbing routines of daily life, this fact of interconnectedness can sound esoteric or quaint. On the road most days, it was a visceral experience, lived and known.

AF: On the road, I was acutely aware of how dependent I was as a human being — constantly and unavoidably dependent, upon the earth, all the elements, people. If it rained, I got wet. If it was hot, I got burned and sweaty and dehydrated. If I was alone, I might feel lonely. I was of my environment in a way that I never had been before … or perhaps just more aware that I was, always had been, and always would be of my environment. What does this mean? It means I am affected by everything that happens in the world, connected to it in obvious ways, subtle ways, and mostly invisible ways that are no less real just because I can’t see them. In cars, in buildings, in the often numbing routines of daily life, this fact of interconnectedness can sound esoteric or quaint. On the road most days, it was a visceral experience, lived and known.

People were a part of the environment, so I got to experience the ways in which everyone I met was a part of me, and I of them. Nowhere was this more obvious than when we sat down to eat together. Here we were, sharing the same food, the same matter, that came from their land, that would flow through both of us, that would become our bodies and fuel our thoughts and feelings and dreams. Moments before, we didn’t even know the other existed, but now we knew, and we were honoring our shared place here in existence by saying yes to our lives, which is, at its core, what eating is: saying yes, again, to being here, in spite of all the struggle, or perhaps partly because of it, because of what the struggle might have in store for us. We would eat and say yes together — to life, to ourselves, to each other. This, to me, was holy communion.

HG: On your walk, there were inevitably times of solitude and quietude. What did you learn from the stillness of being alone with yourself in between interactions with others?

AF: It was in the solitude that I realized I need everyone and no one.

The loneliness of being so alone taught me how ridiculously precious it is to get to spend time with another human being, regardless of who they are, what they’ve done, or what they believe. To not be alive alone! To not be hurtling through the cosmos on this rock on my own, the only human! On those long days and nights in solitude, I got a taste of what that might be like, to be the only human in the universe. Thank God that’s not my fate! Thank God for you! What a joy, what beauty, to spend time in human company. What a gift, to have each other.

Walt Whitman was onto it: “I have perceiv’d that to be with those I like is enough, / To stop in company with the rest at evening is enough, / To be surrounded by beautiful, curious, breathing, laughing flesh is enough, / To pass among them, or touch any one, or rest my arm ever so lightly round his or her neck for a moment, what is this then? / I do not ask any more delight, I swim in it as in a sea.”

To be with you, that is enough. I need nothing else. That’s what I learned in solitude.

But then there was the flip side to that, of realizing that there is a way in which I don’t need anyone else in order to be okay, to be at peace — don’t need their company, or validation, or agreement. I learned how to be alone, insofar as aloneness is even possible given the interconnectedness we share with each other and the Earth. But in the “aloneness,” as this seemingly separate self, this Andrew, I learned that wherever I am, however I am, that is enough. That I don’t have to be anyone else or anything else. That I can welcome all parts of myself. That no voice inside my head is so devious that it can outmatch the healing power of simply being seen. That I just want to be seen and loved, and that I can do that for myself, must do it for myself. Not at the exclusion of receiving it from others, of course, but if I am not actively engaged in the work of understanding myself and loving myself, no amount of understanding or love from someone else will convince me once and for all of my enough-ness. That is a final step that I have to take, that we all have to take: To know we are worthy, not because someone told us we are, and also not because we did something epic once, or made lots of money, or achieved some moral triumph, but simply because we are. Can you accept that? That your worth is intrinsic and unshakeable? That it cannot be diminished or increased? That you are measurelessly valuable, and that that will never change so long as you are you? It’s not what most of us are taught growing up.

HG: In the book, you mention that you never really felt a sense of home in the apartments or houses that you lived in as a child. Where did you feel most at home on the road? How did you come to define the feeling of home?

AF: Home, for me, became the state of being that I was just describing above: this conviction that wherever I was, that’s where I was supposed to be; that however I was — be it beautiful or ugly, graceful or clumsy — that that’s how I had to be, in that moment. Coming home to myself was the end of indulging all FOMO. Fear of missing out betrays a kind of homelessness: Wishing you were at home somewhere else, you become homeless where you are. Can this moment be your home, too? The place where you belong? It needs you, all of you. Listen to what it is asking of you. Here it is, offering itself to your mind to know, and to your body to feel. Will you receive it? Home, for me, became that state of receiving.

Of course, there were plenty of times when I didn’t know how to receive what was being offered to me, or didn’t want to receive the offering. It continues to be a journey, a practice, learning how to come home, again and again and again, one breath after the next, one step after another.

Walking to Listen: 4,000 Miles Across America, One Story at a Time by Andrew Forsthoefel (Bloomsbury, trade paperback, 9781632867001) Publication Date: April 4, 2017.

Find out more about the author at livingtolisten.com.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.