New Carroll & Graf Title Puts a Personal Face on 50-Year Struggle for Equality

|

|

William L. Taylor

|

Just months after Brown vs. Board of Education altered the legal landscape of 1954 America, William L. Taylor landed his first job at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, where he began working for two men who had been instrumental in the landmark case: Thurgood Marshall, then chief counsel of the fund, and his deputy, Robert Carter. Taylor joined Marshall and Carter in working to build upon the Brown victory -- and four years later wrote the Supreme Court brief that led to desegregation in Little Rock, Arkansas, schools.

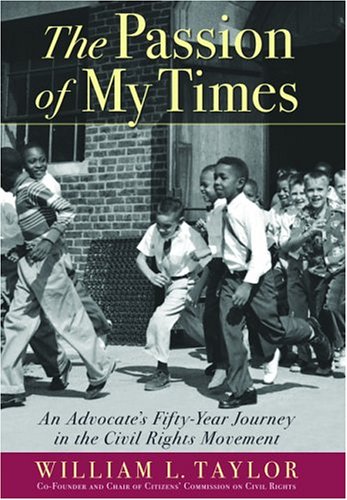

This achievement was one of many in a career that has spanned several decades, and has led Taylor to cross paths with the likes of Martin Luther King, Jr., and John F. Kennedy, as well as countless unknown yet equally memorable citizens. In The Passion of My Times: An Advocate's Fifty-Year Journey Through the Civil Rights Movement (Carroll & Graf), Taylor details these encounters and describes the political and social climate of America from the perspective of someone who has long been entrenched in the quest for equality. His story spans the decades from his first job in the 1950s to his work in the 1960s as general counsel to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights to his current work as chair of the Citizens' Commission on Civil Rights (www.cccr.org) and as a legal advocate for poor and minority children, among other activities.

This achievement was one of many in a career that has spanned several decades, and has led Taylor to cross paths with the likes of Martin Luther King, Jr., and John F. Kennedy, as well as countless unknown yet equally memorable citizens. In The Passion of My Times: An Advocate's Fifty-Year Journey Through the Civil Rights Movement (Carroll & Graf), Taylor details these encounters and describes the political and social climate of America from the perspective of someone who has long been entrenched in the quest for equality. His story spans the decades from his first job in the 1950s to his work in the 1960s as general counsel to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights to his current work as chair of the Citizens' Commission on Civil Rights (www.cccr.org) and as a legal advocate for poor and minority children, among other activities.

The author (who also wrote Hanging Together: Inequality in an Urban Nation, published in 1971) is a busy man, and perhaps that had some bearing on his finishing The Passion of My Times in about 18 months. "It's amazing it went that fast," he said. "I thought about it a long time before I set words to paper and discovered I'm better organized than I thought. I had briefs and memos from working with Thurgood and with the Kennedy administration. The Commission took terrific minutes of meetings, too, so I was able to occasionally reread what I'd said [at these meetings]."

And, upon reflection, he said, "When I started, I didn't know much about the race issue and thought the Supreme Court would issue a great decision, and I'd be getting on the bandwagon and be able to change things around the country. Ultimately, I realized how much more complicated it was."

For example, regarding the government's influence on housing segregation, Taylor noted, "In the 1930s and 1940s, the government was working hand in glove with the housing industry to keep housing segregated. The residual patterns of segregation that exist today are in many ways a product of those old policies. In fact, the notion that real estate brokers are adversely affecting values of housing if the housing is racially integrated was written into the law of some states."

And, he added, while many people may be aware of this state of affairs, "they think of it as ancient history and are not ready to connect the dots with current situations." The Passion of My Times will surely add depth and color to readers' perceptions of recent American history and the ways in which the mores of the recent past still strongly guide standards of living, education, and finances for people today.

This lack of awareness is not new, of course. Taylor noted that the Civil Rights Commission, established in 1957, was part of the first civil rights activism since Reconstruction. He added, "The federal government was not really prepared to do much about civil rights, but thought they at least ought to study it. It was set up to be bipartisan, and to simply investigate and report."

And, he said, "It didn't get off to a promising start because President Eisenhower named [to the Commission] Southern Democrats, former Democratic governors who were part of the era of segregation, and Republicans who didn't have a real history in working for civil rights."

It is this sort of insider's-view that helps make The Passion of My Times more than just a chronicle of one man's career during a tumultuous and important time in American law and politics. Taylor's voice rises to the surface as he describes the events of his childhood and when he speaks of his late wife, Harriett, herself a Superior Court judge and a person unafraid of defying convention (check the last chapter for a fascinating recounting of Senator Orrin Hatch's angry reaction to Harriett's ruling in a 1994 custody case).

In addition, he provides wry commentary about the vagaries of legislation, as well as the challenges to civil rights that came -- and continue to come -- in the form of those who are not interested in striving for equal rights, from governors to judges to average citizens.

"One thing that is universal is that some people, including young people, have a sense of entitlement," Taylor reflected. "That's part of what the book is about -- people feel entitled to the privileges they enjoy, and never reflect on who they're stepping on to maintain those privileges."

However, Taylor said that he does have a good feeling about the young people he encounters today, and "how much more easily people adapt to diverse situations in the classroom and other situations without giving it another thought."

It is this adaptability, he explained, that should give us confidence that individuals can effect change. "People can do more than they probably think they can. There are all these people who have become fiscally independent and have careers and so on, and they say they're unhappy with their communities because they aren't diverse. It strikes me, if people can organize their lives -- which is pretty hard -- they can do more by their own efforts than they realize."

Taylor's efforts include touring to promote The Passion of My Times -- including a stop at his neighborhood bookstore, Politics and Prose in Washington, D.C. -- and continuing his work in Missouri, where he has been working on school reform issues since 1980. "We've been able to accomplish things there that haven't happened elsewhere, such as metropolitan school desegregation.… It's been a lot of hard work."

Not that that's ever stopped him, of course. After all, said Taylor, "If you open up yourself to new experiences, all sorts of interesting things can happen." --Linda M. Castellitto