- Categories:

Inside the Walls of The Glass Castle

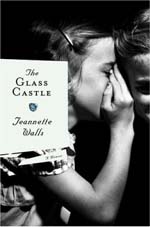

To stand out in the current sea of memoirs isn't easy, but with fine writing and a compelling story, Jeannette Walls' debut memoir, The Glass Castle (Scribner), is winning rave reviews. From her nomadic, unusual, and difficult early life to her current success as gossip columnist for MSNBC.com, Walls provides a balanced portrayal of a family led by parents who themselves were prone to extremes. The book was chosen by independent booksellers as a March Book Sense Pick and has garnered starred reviews from Kirkus and Publishers Weekly.

To stand out in the current sea of memoirs isn't easy, but with fine writing and a compelling story, Jeannette Walls' debut memoir, The Glass Castle (Scribner), is winning rave reviews. From her nomadic, unusual, and difficult early life to her current success as gossip columnist for MSNBC.com, Walls provides a balanced portrayal of a family led by parents who themselves were prone to extremes. The book was chosen by independent booksellers as a March Book Sense Pick and has garnered starred reviews from Kirkus and Publishers Weekly.

Walls, who recently spoke with BTW by phone from Manhattan, said of the reception, "I was blown away. I was overjoyed and overwhelmed. When you write something like this, you have no idea how it will be received. So many books that come out never get any sort of attention at all."

The Glass Castle begins in the present with Walls, who is living in a Park Avenue apartment, on her way to a fancy Manhattan party when she sees her homeless mother digging through the trash. Her achingly compelling narrative tells how each reached such a destination.

Walls' memoir follows her family's chaotic life from the 1960s through the early 1990s as they meander through Arizona, Nevada, California, a "vile hamlet" in West Virginia, and, ultimately, New York City. Along the way, they get stung by scorpions, shot at, and chased by the police. Often in the middle of the night, Walls' father, Roy Walls, would announce, "Time to pull up stakes and leave this shit-hole behind." Everyone would have 15 minutes to do the "skedaddle."

The Walls' parenting skills ran the gamut from dangerously negligent to warm and wise. Being allowed to pet a cheetah through the bars of its cage was not out of the ordinary, and Roy would go on multi-day alcohol-fueled benders and rages, while the family went Dumpster diving for food.

But the Walls also shared many experiences of love. Walls writes of how on one Christmas, Roy took each of his children out into the desert night and gave them each a star, or a planet, complete with an astronomy lesson. Walls recalls how she picked Venus and felt sorry for kids who just got "a bunch of cheap plastic toys." Her father told them, "Years from now, when all the junk they got is broken and long forgotten, you'll still have your stars."

|

|

For almost 20 years, Walls had attempted to complete the memoir, each time throwing away the manuscript. In 2000, she began working on the current version. As she explained, "I hammered it out in about six weeks, but the voice was much too distant. I had written it as though [I were] a reporter writing about someone else. So I wrote it from the perspective of a little girl, what she felt and thought at that time." Walls credited her editor, Nan Graham, with helping her maintain that voice consistently.

Part of what stymied her writing process was that Walls had long kept her family life a secret. She also hid the fact that her parents were living in New York and were homeless, although she had tried helping them numerous times. Walls was working as a reporter, covering Manhattan's movers and shakers, which she still does, and was concerned what they would think. "Even when we were living in West Virginia I hid the extent of how bad things were," she said. "Even then, I didn't want people to know, because I was afraid I'd be ostracized more than I already was. In New York, I carried over that fear, that if people knew, I would somehow have been disqualified.... I was afraid of what people would think if they knew my parents were [homeless], while I was living the life that I was."

Reactions to the book's publication, however, have surprised her. "'Its been an incredible epiphany for me. You let your secrets out and people don't run from you, they bond with you in a way. People do understand. They have a greater capacity for compassion than I realized."

Walls' husband, John Taylor, who is also a writer, helped her overcome her apprehension. "My husband was amazing. He, more than anyone, was the one who said, 'You must write this.'" As Walls said in her dedication, Taylor convinced her that "everyone who is interesting has a past."

Once she was convinced, "it just became a matter of telling the story," said Walls. "The book evolved, and I don't want to say it wrote itself, but in a way it did. I can't take the credit because my dad has all the great scenes, and my mom has all the great lines. It was a fascinating process and, as I wrote and rewrote, the patterns and themes really presented themselves."

Walls developed a strategy to reveal intimate details about her family's intense struggles. "I pretended nobody was going to read it, because I was afraid I wouldn't be honest enough," she said. "But what has been shocking to me is the number of people who have connected with the little girl -- the little girl being me, of course. I'm overjoyed."

As a family, the Wallses have always been tightly knit, and this continues with their support of The Glass Castle. Beginning with the early drafts, her brother served as a sounding board and her sisters loved it, although the youngest finds some of it embarrassing. Her father died long before the book was published. Rose Mary, Walls' mother, despite being depicted as the anti-June Cleaver, is ebullient. "I've got to say she's been great," said Walls. "I think she's enjoying the publicity more than I am. Bottom line, she really believes in telling things as you see them."

When asked if she missed the peripatetic lifestyle, Walls said "no" without hesitation. "I do like having some excitement in my life, that's the reason I like journalism and the city, but I also like a great deal of stability. I love the feeling of having a home, a place where you belong. I don't have my parents' nomadic impulses. I've realized you can have mobility, excitement, and have a house at the same time," she said, laughing. "It's a question of balance. My parents didn't aspire to that balance. They liked extremes." --Karen Schechner