- Categories:

An Indies Introduce Q&A With Samira Ahmed

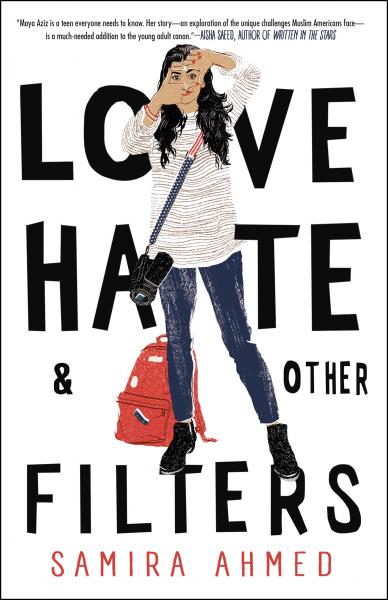

Samira Ahmed is the author of Love, Hate & Other Filters, a Winter/Spring 2018 Indies Introduce debut title for young adults and a Winter Kids’ Indie Next List pick.

Samira Ahmed is the author of Love, Hate & Other Filters, a Winter/Spring 2018 Indies Introduce debut title for young adults and a Winter Kids’ Indie Next List pick.

“This compelling contemporary read features an unapologetic Indian-American heroine trying to navigate crushes, dreams for her future, and the expectations of her family in a world where her culture is routinely misunderstood,” said Rebecca Wells of Porter Square Books in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who served on the Indies Introduce panel that selected Ahmed’s debut. “A timely read that deftly tempers difficult topics with levity and a wonderful narrative voice!”

Ahmed was born in Bombay, India, and grew up in Batavia, Illinois. She’s lived in Vermont, New York City, and Kauai, and currently resides in the Midwest. A graduate of the University of Chicago, Ahmed taught high school English for seven years, worked to create more than 70 small high schools in New York City, and fought to secure billions of additional dollars to fairly fund public schools throughout New York State. Her creative nonfiction and poetry has appeared in Jaggery Lit, Entropy, the Fem, Claudius Speaks, and the Spine Out novelist series.

Here, Wells talks to Ahmed about the inspiration for her debut, the timeliness of main character Maya’s story, and what she’s working on next.

Rebecca Wells: You’ve done a lot of great work outside of writing. What inspired you to start writing, and to write Love, Hate & Other Filters, in particular?

Samira Ahmed: I always wrote, even when I was a kid — especially poetry. A lot of angst-ridden, lovelorn poetry. But I was never the kid who dreamed of being a writer when they grew up. I had other dreams — ones that I pursued. I always loved writing, though. And when Maya came to me — her story was inspired by an amalgam of events, namely prejudice I faced as a young child and the rise of Islamophobia after 9/11 — she fixed herself in my mind and wouldn’t leave. I first wrote a short story about her and then realized that maybe her story was a book. So I wrote it. Then I put a draft in my drawer and would occasionally tinker with it. Life happened, years passed. But Maya’s story and her voice stayed with me. I finally decided to give her story the attention it merited. I often thought of my former high school students when I was working on it. I once taught in a district with a very large immigrant population — over 50 languages were spoken there — and each of those kids had a story, but those stories rarely made it to the page. Maya’s story is not any of their stories; it is uniquely her own, but all those stories deserve to be told and heard.

RW: Maya is a personable teenage character with very relatable dreams and views, and I love the way she balances her personal desires with her love for her family and the Indian community. Is she inspired by anyone specific?

SA: The short answer is no.

Rather, Maya was inspired by many of the teenagers I met when I was a high school teacher, and also, in a small way, by the teenager I was. The tension Maya feels between the dreams she wants for herself and the expectations of her parents is very much a natural one — I experienced it. I think most kids do. For those of us who grew up in immigrant families, it may be a more liminal tension. More ever-present. And, in some ways, more poignant. A child always grows away from their parents. That is the job of a parent — to give their child the tools to be independent. But for the immigrant family, there’s a different cost to it, an inevitable cultural loss that happens as the first generation gives way to the second and then the third, as this once-new nation becomes (hopefully) fully your own. As you plant yourself here. There’s this great poem by Michael Ondaantje, “What We Lost,” that, for me, really captures the poignancy of what I’m talking about. Maya loves her family and loves her culture and when she finds her parents’ wishes at odds with her own, she wonders what she will inevitably lose to pursue the life she imagines.

RW: While Maya is the primary narrator, there are also other points of view throughout the book that create a strong sense of foreboding from the first chapter. How did you come to include these?

SA: The intercalary chapters were inspired by two very specific sources. First, and perhaps most obviously, the intercalary chapters of The Grapes of Wrath. I was really blown away by those chapters when I read that book. They seem at first to have nothing to do with the Joad narrative, and yet as they go on, you can see how they fit as part of the big picture. Steinbeck himself said the basic purpose of those chapters was “to hit the reader below the belt.” He added, “It is a psychological trick if you wish but all techniques of writing are psychological tricks.” I couldn’t agree more.

The second inspiration, which speaks more to tone than structure, is a line from Capote’s In Cold Blood: “Presently, the car crept forward.” I cannot state strongly enough the brilliance of this line. It is five simple words and yet so ominous, and those words instill such fear in the reader. I had an almost visceral reaction to that sentence. I knew what was going to happen next, of course. It’s a work of nonfiction based on an infamous crime, yet there I was, willing that car not to creep forward. Wanting to step into the book and back in time to stop it all from happening. But, as we know, it was inevitable.

RW: Love, Hate & Other Filters is an extremely timely book. Do you have any advice for young readers who may be in a similar position to Maya as members of a marginalized community in the United States — or for readers who want to help?

SA: My heart aches for those kids — knowing the often-hostile world they are facing, the intolerance and cruelty being tweeted into this country on a near daily basis.

I need to say that I’m not a mental health professional. I am not qualified to give professional advice.

I speak solely from my own experience as someone from a marginalized group and as a former teacher.

That being said, first and foremost, to any one who is feeling physically threatened, please tell someone right away — your parents, if you can, or other adults you trust, your teacher or school administration or police, if you feel safe doing so. There are also a variety of anonymous hotlines available to you that can offer resources and help, sometimes in your own community. Someone physically threatening you is never okay.

I would also like to add that you are not alone and please seek help if you need it. All around you there are others who have been through this, who are here to help lift you up. Look for the helpers. And please know that you are loved and wanted and that you, as an individual, are so important, that you have a contribution to make and that your voice deserves to be heard. You are enough.

Sometimes just the day-to-day can be so hard. Please take care of yourself — of your physical, emotional, and mental health. If social media is too toxic, step away. Same for real-life friends. No one should make you feel bad about yourself; if they do, they don’t deserve your time or your love or your loyalty.

For readers out there who want to help, let me just say, being an ally means you need to be active. It’s not enough to be non-racist. You need to be anti-racist. It may not be easy, but you need to use your voice and your privilege in the moment to speak up when you see something wrong being done. Even if it is “only” a microaggression. Obviously, you need to make sure the situation is safe for you. And there will be times where you might feel uncomfortable — just imagine how the person on the receiving end of that hatred feels at that moment. I assure you, it is far more than uncomfortable. I think Marlon James did a great job explaining the difference between being a non-racist and an anti-racist. It’s worth your two minutes.

Speak up, stand up, call your elected officials, vote, march. Do you believe America should be a nation with liberty and justice for all? Then you need to actively create that world.

RW: Can you share anything about what you’re working on next?

SA: My next book with Soho Teen is tentatively titled Mad, Bad & Dangerous to Know. I’m having so much fun writing it. I’m thrilled to be working with my editor, Daniel Ehrenhaft, and the entire Soho team again. Mad, Bad & Dangerous to Know (apparently all my book titles will have ampersands) is a literary mystery that follows the story of a young Indian-French-American-Muslim girl who is on her annual vacation in Paris with her family when she meets a swoony young man who is the descendant of Alexandre Dumas. Together they search for the identity of a mysterious 19th century Muslim woman who appears in correspondence between Dumas and the painter Eugene Delacroix. It’s a dual narrative novel that weaves together past and present and ponders questions about love and identity and the passage of time.

Love, Hate & Other Filters by Samira Ahmed (Soho Teen, 9781616958473, Young Adult, $18.99) On Sale Date: 1/16/2018.

Learn more about the author at samiraahmed.com.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.